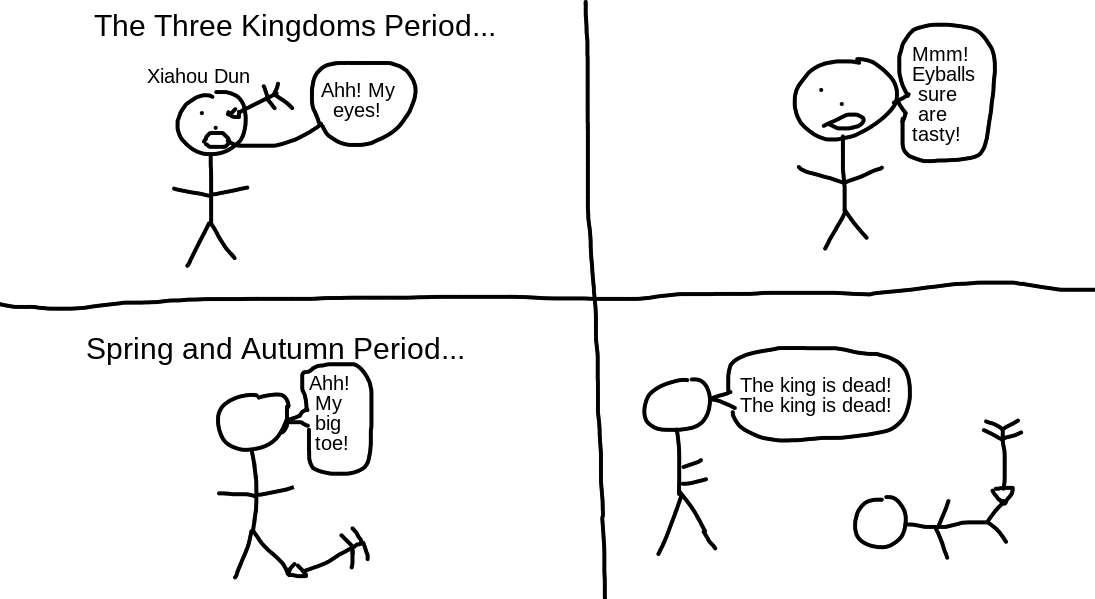

Spring and Autumn Period

Welcome back! We ended off our last post at the fall of the Western Zhou Dynasty (西周) when its final king had his capital and much of his army obliterated by barbarian tribes. We now hop back into the story at a time of crisis.

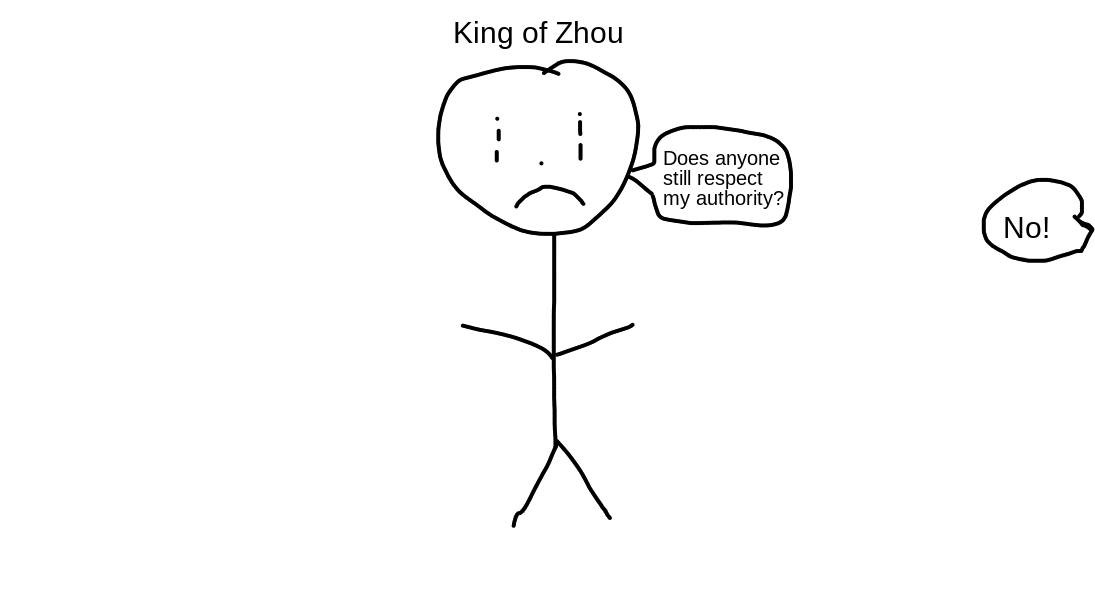

A new king, King Ping (周平王), moved the capital eastward, to a city called Luoyang (洛阳). This continuation dynasty was aptly named the Eastern Zhou Dynasty (东周).

Although the royal bloodline survived, its authority did not.

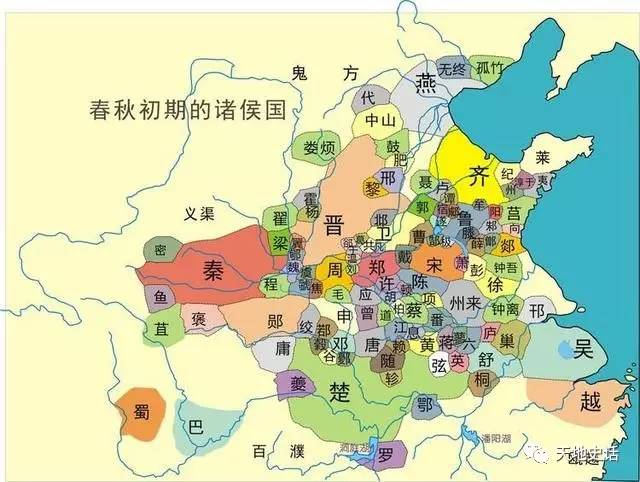

Remember that map from the previous post showing what China looked like at the end of the Western Zhou Dynasty? Don’t remember? Well, here it is again.

Each of these kingdoms, remember, was handed out as a fief to a variety of nobles, and could be passed down through heredity. Over time, citizens in each fief identified less as “a subject of the Zhou king” and more “a subject of a Duke of Qi,” or the “Duke of Jin,” or maybe even the “Viscount of Chu.”

Now that the Zhou had no authority to restrain these ravenous kingdoms, it pretty much became a free-for-all, as every kingdom tried to conquer every other kingdom and build its own strength. Now, I’m not gonna do that cringy thing that YouTubers do where they ask their viewers who they think is gonna win this thing. After all, everyone could just scroll down and figure it out in like 3 seconds. But, I’d like all of you reading to place your bets, out of all of these kingdoms, on which one you think will come out on top, and remember it until you finish this post. Let’s see how far you can make it before your kingdom is eliminated, or whether you win this whole thing! Don’t peek!

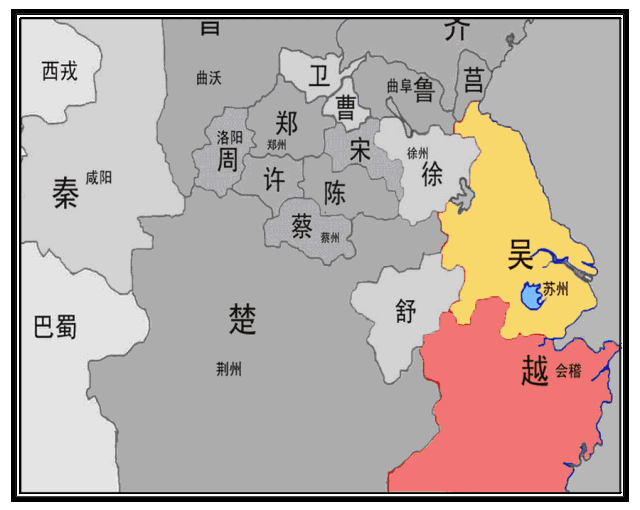

(To expedite the process, because I assume many of you can’t read Mandarin, I will simplify and just tell you that the winner will be one of the bigger kingdoms. So here they are: Chu (楚), Qi (齐), Jin (晋), Song (宋), Qin (秦), Yan (燕), Wu (吴), and Yue (越). Pick a kingdom, locate that kingdom, and let the games BEGIN!)

But before we get into exciting war stuff, here are some basic facts about this period.

Eastern Zhou Dynasty:

Began: Around 770 BC

Ended: 256 BC (This is actually a date we can be sure of!)

Alternative name: Spring and Autumn Period (for the first 300 years) and the Warring States Period (for the latter 200)

Capital: Luoyang

Central Authority: None

Technically, there are supposedly only 5 hegemons. However, there is some dispute over who they are. There are three who are undisputedly considered hegemons, and there are two other positions that are filled differently depending on who you ask. There are broadly two perspectives on who the five hegemons were, explaining why there are 7 hegemons. I will discuss all seven, and point out the four that are disputed.

For the first 300 years of this rump dynasty, alternatively known as the Spring and Autumn Period, de facto power actually fell into the hands of “hegemons” (霸主). Every few decades, when a warlord became powerful enough, gained enough respect, or was legitimized ceremonially by the Zhou king, he would be regarded as “hegemon” by his fellows. Throughout the Spring and Autumn Period, 7 “hegemons” would emerge. Our narrative will unfold from their perspective

Duke Huan of Qi (Ruled 685-643 BC)

The first hegemon was Duke Huan of Qi (齐桓公). His hegemony is undisputed. His real name was actually Xiaobai (小白), which translates into “Little White.” It’s actually a really cute name in Mandarin.

Xiaobai’s succession to the throne of the kingdom (or I guess, the duchy at this point) was far from guaranteed. In fact, when he was quite young, his dad died and his brother got murdered. So he was forced to flee to the neighboring kingdom of Lu (鲁) for refuge. When his cousin, who succeeded his brother as Duke, also got murdered, (this family is literally more dysfunctional than the Kardashians!) Xiaobai, now one of the few remaining members of the ruling House of Jiang, raced back to Qi to claim the throne. However, he faced competition from his older brother. Whoever could reach the capital and consolidate power first would become the duke. The other would probably die, and they both knew that. So, a race ensued. When the two, each with their own entourage, chanced upon each other, and the following scene ensued.

The artistic depiction is slightly inaccurate. The older brother did not actually fire an arrow toward his younger brother, his advisor and teacher Guan Zhong (管仲) did! Fun fact: Duke Huan of Qi was later convinced by his close confidants not only to spare Guan, but even to promote him to the position of High Chancellor (essentially a Prime Minister in our day)!

Turns out, when Xiaobai was shot, it miraculously hit his metal belt buckle, and did not damage his flesh. But in a moment of genius, he bit his tongue, drew blood, then spit it out and fell from his horse, making his brother, who was too far away to see the minutiae of the situation, believe he had died. Assuming he had killed his competition, the older brother began to leisurely progress towards the capital, while Xiaobai hurried by night.

Xiaobai ended up ascending the throne first and became Duke Huan of Qi. His brother was, unsurprisingly, eliminated soon after.

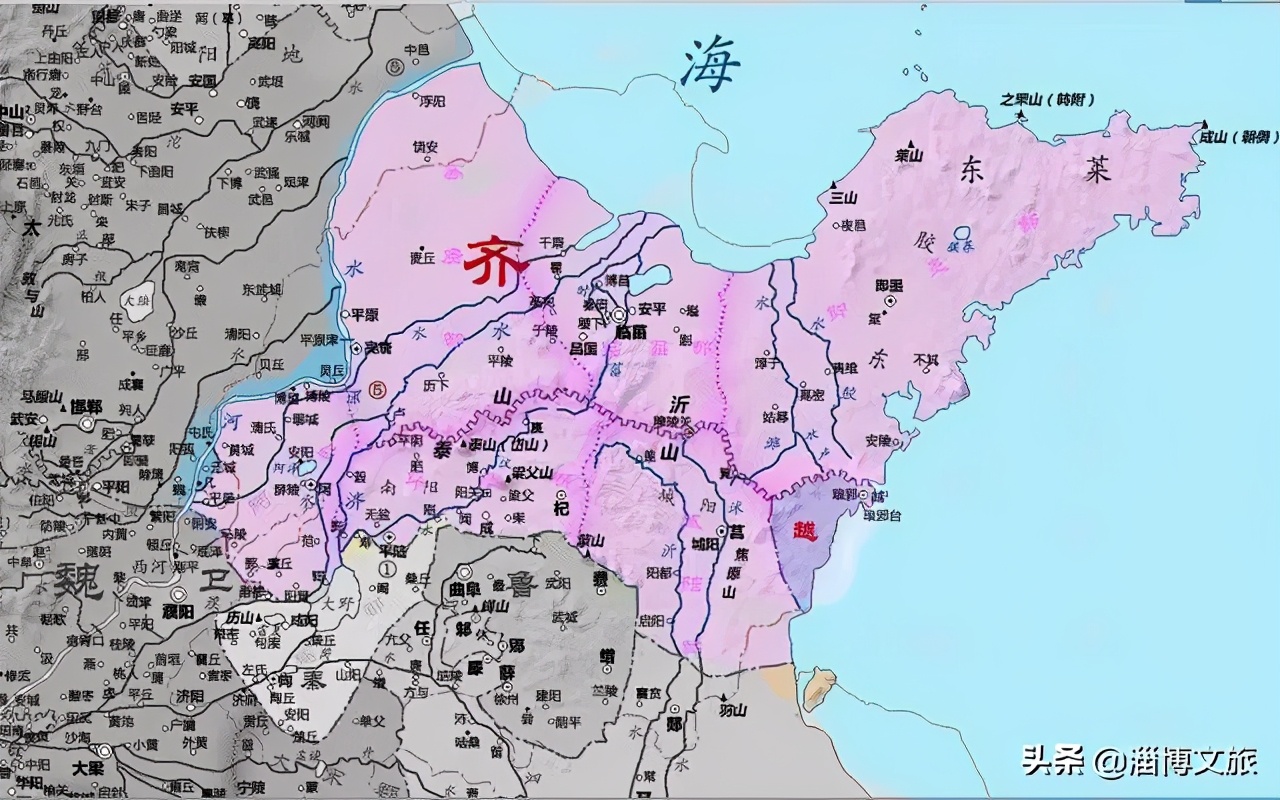

The kingdom of Qi was unique compared to other kingdoms because it did not derive its wealth primarily from agriculture. Instead, due to its adjacency to the Pacific Ocean, Qi merchants controlled the salt and fish supply. Just as many African kingdoms grew rich in the Saharan salt trade, so too did Qi grow rich in this trade. It shows that despite being in completely different environments, humans still basically want the same things.

OK, but how does Xiaobai go from the duke of one region to hegemon? Well, it was a combination of both strength and generosity. Due to its proximity to the Pacific Ocean, Qi had an abundance of fish and salt, which it used to grow rich and finance a strong military. In one expedition, Duke Huan aided his northern neighbor, Yan (燕), in battle, scoring multiple victories and conquering many cities. But rather than claiming these cities for Qi, he handed them over to Yan. This gesture of generosity, combined with, you know, Qi’s ability to kick everyone’s ass, led warlords from across China to name Duke Huan “hegemon.”

Duke Huan reigned for 43 years, conquering many smaller neighbors and creating an era of prosperity for Qi. But Qi’s hegemony did not last long after Duke Huan was starved to death by his own children in 643 BC.

And I will not be elaborating on that incident further.

Duke Xiang of Song (650-637 BC)

Song (宋) is the dark-orange one. The big green blob to its south is Chu (楚)

Now time to introduce the second hegemon, Duke Xiang of Song (宋襄公). His kingdom, Song (宋), was in China’s fertile central plains. He ruled nearly concurrently with Duke Huan, and even sent troops to stabilize Qi after it descended into chaos following Duke Huan’s death.

The Song (宋), if you look at the map, was located near the center of the country, in the Yellow River Basin. This area was historically known as the “central plains,” or Zhong Yuan (中原), and it would be where much of China’s wealth would be concentrated for the next 2,000 years. Being in this strategic location, Song not only had fertile soil for agriculture but also dominated trade between kingdoms, and consequently grew rich despite not having a sizable military or a massive population.

Duke Xiang’s hegemony is disputed. Some argue that he was a hegemon because he commanded the respect of a multitude of warlords. Others disagree because, well…how do I put this diplomatically? He was not the sharpest tool in the shed.

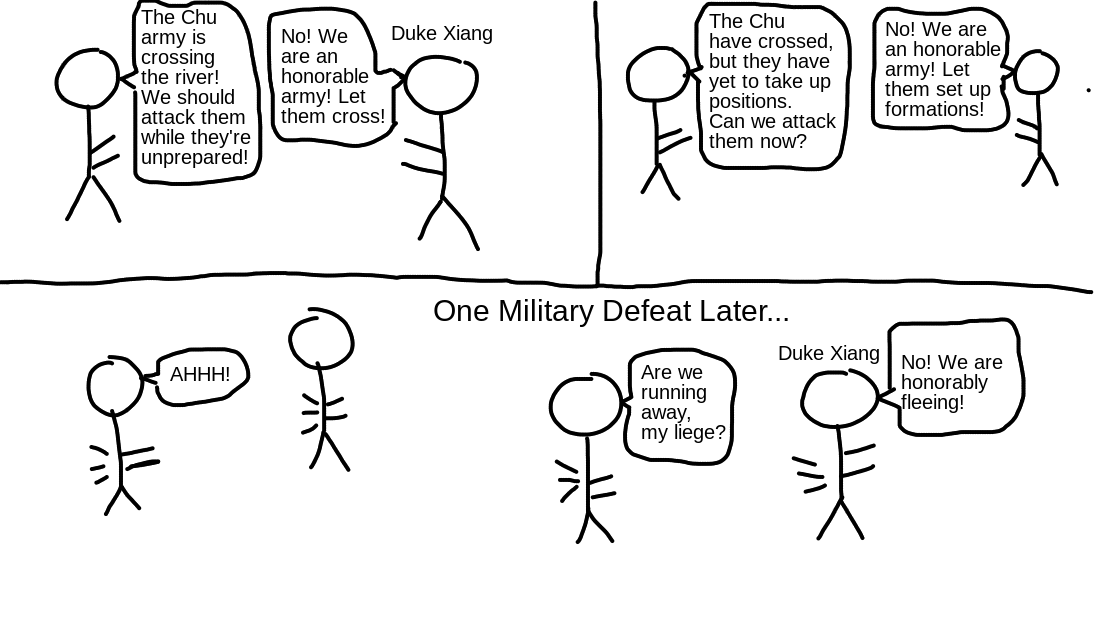

In one instance, soon after Duke Xiang was declared hegemon by a few of his smaller neighbors, the kingdom of Chu (楚) to its south decided to invade, partially because Chu wanted Song’s fertile land and strategic location, and partially because Chu’s king wanted to be hegemon as well.

Duke Xiang immediately led his forces out to meet the invaders.

The Song army assembled their battle lines on the Northern banks of the Hong River (泓水) facing the opposing army. The Chu, eager to win a quick victory, crossed the river to get at the Song military. At this time, any intelligent military tactician would recommend firing arrows at the crossing army, since they were in exposed rafts, and were in no position to fire back. But Duke Xiang prided his army on being the most honorable in all of China. “No cheap tricks” was his motto. So when the battle commenced, he did this:

Although the Song kingdom (or duchy, I guess) survived this ordeal, its strength was severely crippled. It would never become powerful or relevant again for the rest of its existence. Around 400 years after Duke Xiang’s death, in 285 BC, Song was carved up by its neighbors.

Song (宋): Eliminated

Duke Wen of Jin (636-628 BC)

The Kingdom of Jin derived its power from two sources. Firstly, due to its early expansion, it had large amounts of farmland in the fertile “Zhong Yuan.” Secondly, its proximity to the Zhou King gave it political leverage. After all, even though the Zhou king no longer had any de facto power, he still held the title Son of Heaven.

The third hegemon, (or second, if you don’t think Duke Xiang deserved to be one), was Duke Wen of Jin (晋文公). His hegemony is undisputed because he was literally a chad.

In 637 BC, a noble from the Kingdom of Jin (晋) named Chong Er (重耳), fleeing from political strife in his country, took refuge in Chu (楚), and was sheltered by its king. To repay this kindness, Chong Er promised that if he ever became Duke of Jin (a pipe dream at the time), and his kingdom was engaged in war with Chu, he would retreat 90 li (a Chinese unit of measurement) as a gesture of peace. Only if the Chu army pursued him would he then order his troops into battle.

In a turn that should shock literally nobody, just a few years later, Chong Er was crowned Duke Wen of Jin. He then proceeded to bolster the kingdom’s strength until it was on par with Chu. This inevitably set the two kingdoms on the path to conflict.

After Duke Xiang of Song got his rear end handed to him at the River Hong, that same king of Chu decided to launch a second invasion not long after to take over the entire kingdom. Duke Wen sent reinforcements to rescue Song, not wanting Chu to win all that fertile territory and become an unbeatable force.

But, as promised, when the Jin army met their Chu counterparts on the battlefield, Duke Wen ordered his forces back a full 90 li as a gesture of peace. “Don’t attack me,” Duke Wen seemed to chide, “and nothing bad will happen.” But although Duke Wen remembered his promise, the King of Chu forgot all about it.

Duke Wen fulfilled his promise and also kicked his opponent's ass in one fell swoop! Absolute chad!

This story is so famous in China that it even has its own idiom: 退避三舍, meaning a retreat of 90 li. It has been used to mean taking a step back and giving up some of your interests in hopes of a compromise.

Now having secured his kingdom as the most powerful militarily, he was generally unimpeded in strengthening his kingdom’s economy and enhancing its political clout. Warlords from all corners of China came to regard him as the preeminent duke, and the King of Zhou bestowed upon him the title “hegemon.”

Although historians of this time often only record the records of dukes and kings, it is likely that thousands, if not millions of unrecorded lives were lost in the centuries of ceaseless bloodshed that marred the reign of the Eastern Zhou Dynasty. It would be this suffering that would inspire philosophers like Confucius, Lao Tzu, and Sun Tzu, among thousands of others, to seek stable government and peace in the world. The philosophies of Confucius, in particular, which emphasized respect and absolute fealty to rulers, would define and bolster imperial power for centuries to come.

Anyway, dark and depressing stuff aside, let’s move on to the stories of the remaining hegemons!

Duke Mu of Qin (659-621 BC)

Ruling concurrently with Duke Wen was Duke Mu of Qin (秦穆公). Qin (秦) was the furthest west of all the major Chinese kingdoms, and it shared a long border with Jin. Duke Mu was the fourth hegemon, yet this position is contested.

Duke Mu had quite an amicable relationship with Duke Wen. In fact, he had actually assisted Duke Wen in his ascension. Peace on his eastern border allowed Duke Mu to rapidly expand to the west, conquering many nomadic tribes and incorporating them into his own forces.

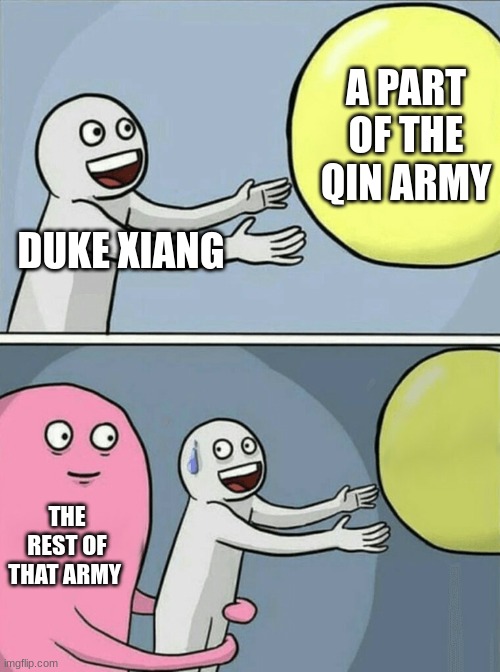

But of course, Duke Mu would not have even been considered for the position of hegemon unless he kicked some ass in the east as well. After Duke Wen’s passing in Jin, his son, Duke Xiang of Jin, (there were a lot of Duke Xiangs) broke the truce with the Qin, and launched a surprise attack against the kingdom. After annihilating a Qin army in an ambush, Duke Xiang’s head became filled with dreams of conquering Qin, and becoming even more powerful than his father. Of course, Duke Mu would have none of it.

A few years later, Duke Mu attacked Jin in revenge. His troops, hardened by years of combat, trounced their foes. This defeat, not long after Duke Wen’s death, would precipitate a period of decline for Jin.

Duke Mu was a pragmatic leader, however. Understanding he lacked the strength to push deeper into Jin territory, he retreated with his loot and dedicated the remaining years of his reign to unifying the west. This is precisely why his hegemony is disputed—his power was largely marginalized to China’s western fringes.

King Zhuang of Chu (613–591 BC)

The fifth hegemon was King Zhuang of Chu (楚庄王). His position is not disputed.

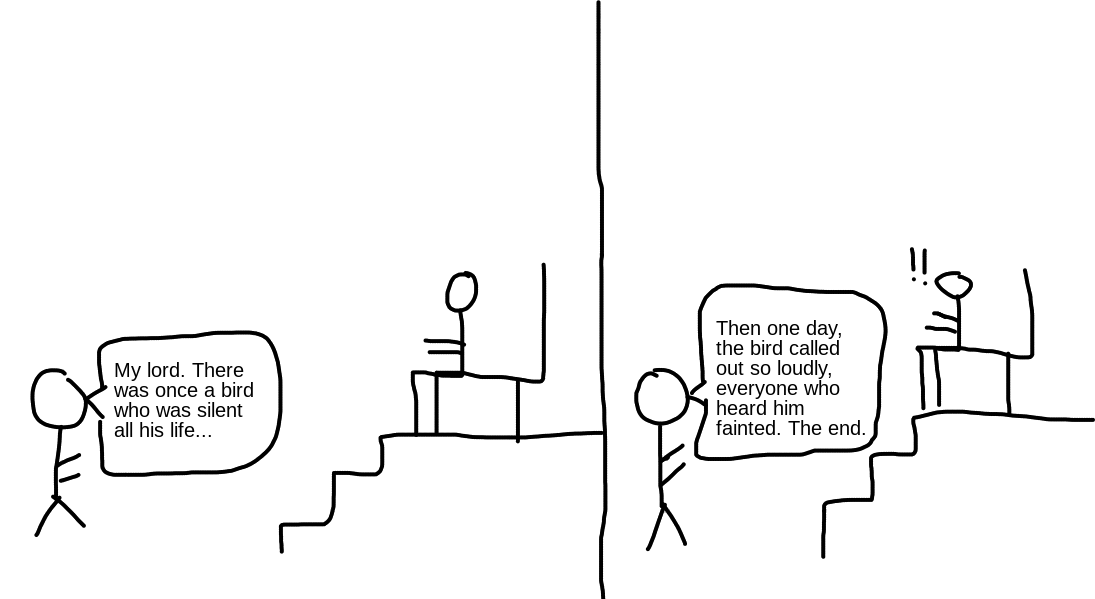

Unlike other rulers, King Zhuang was not a wise ruler upon ascendancy. In fact, early in his reign, he would often be found drunk in his palace, with a lady coddled in each arm, stubbornly refusing to deal with the matters of state. So in order to make him change his ways, one of his advisors related this story to him:

Not once did the advisor explicitly ask the king to focus on his duties. Yet the king understood his message immediately. His advisors appealed to the king’s inner desire to be remembered in history, and to show his ambition through perseverance and hard work. Soon afterward, he changed his ways and ruled with firmness and strength. Under him, Chu's economy boomed.

But besides strengthening the economy, King Zhuang had one more unquenchable desire: beating up the Jin army.

Fortunately, by this point, Jin was far from the powerhouse it was under Duke Wen, especially after its reckoning at the hands of the Qin. At the Battle of Bi (邲之战), the Chu killed so many Jin troops that they even considered building a temple filled with their decapitated heads.

By the time of King Zhuang’s death, many of the smaller kingdoms, which you may remember made that first map almost impossible to read, were eliminated by larger neighbors. Here’s what China looks like now.

You’ve probably noticed that China during the Spring and Autumn Period is not the China we know today. The “western fringes” of China during this period would have been the Sichuan Basin, an area that today would be considered central China. Nevertheless, China’s population today is largely concentrated in the lands which belonged to the former Zhou Dynasty.

You’ll notice that the traditionally powerful kingdoms of Jin (晋), Chu (楚), Qi (齐), and Qin (秦) have grown in size, and are now the undisputed rulers of their respective regions. Yan (燕) is still there in the Northeast, chillin’ out (Get it, 'cause it’s so cold up north? Haha, my puns are so funny.)

Without a powerful hegemon in place after King Zhuang’s passing, each of these large kingdoms weakened each other through conflicts with each other. In this time of turmoil, an unlikely power would emerge.

King Helu of Wu (514-496 BC)

The Kingdom of Wu (吴) was historically a small, marginal power. Located adjacent to the Pacific Ocean, with the powerful kingdom of Qi (齐), to its North and the enormous kingdom of Chu to its west, and Yue (越) to its South (which this map does show), Wu was often seen as a contained, and thus negligible, power.

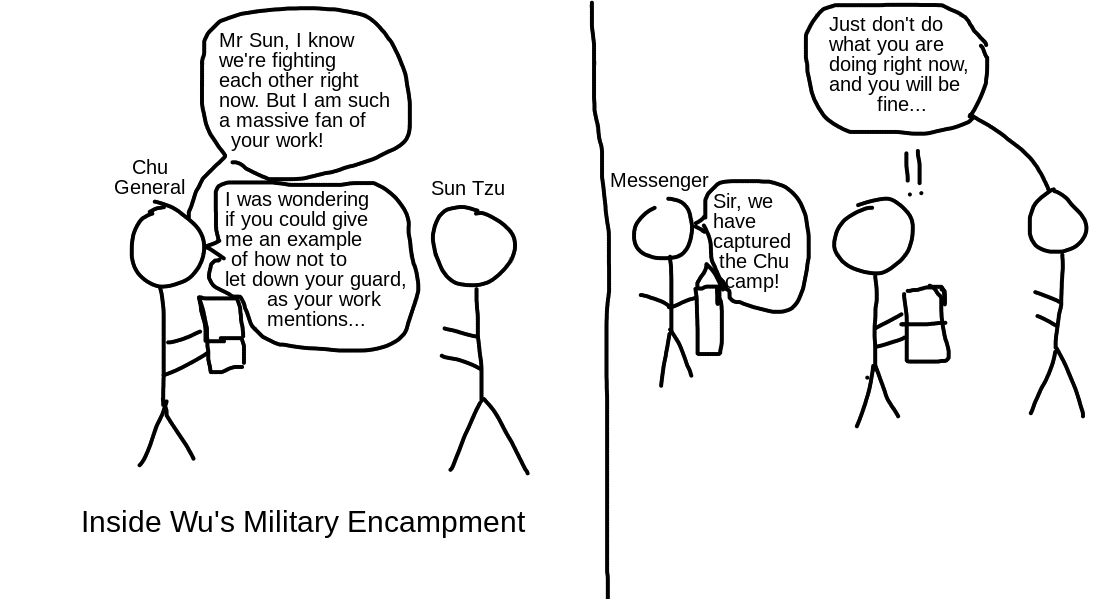

But in being neglected, few nations noticed that it was quietly gaining strength. Under King Helu (阖闾), who took power less than 80 years after King Zhuang’s death, the king attracted to his court a pretty famous general known as Sun Wu (孙武), a man better known today as Sun Tzu.

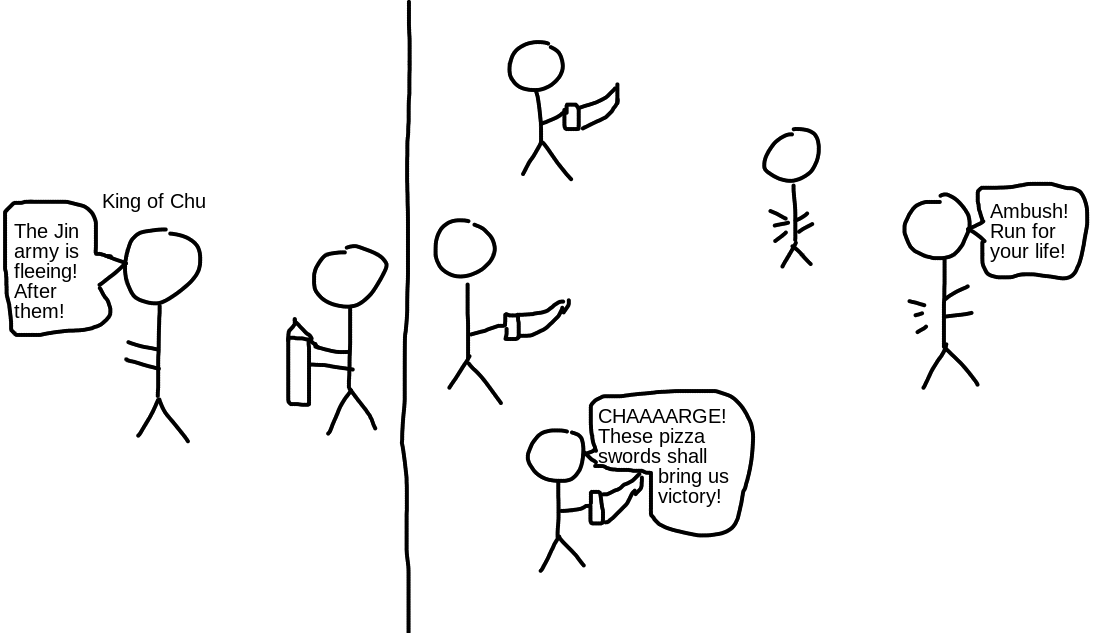

Once he was in command of King Helu’s army, Sun Tzu led them to war against the Chu. As the author of The Art of War, it’s unsurprising that Sun Tzu himself was quite proficient in that art. Furthermore, many Chu generals were learning how to command an army using The Art of War. So you could probably guess what happens next.

(Note: the above image is a satirical exaggeration, not a historical account)

Chu's commanders attempted to follow the book’s rigid advice to the letter, hoping that their numerical superiority would prove decisive. Sun Tzu, by contrast, knew all the loopholes. Again and again, Chu armies larger than that of Wu’s were routed until the kingdom’s magnificent capital fell to the invading forces.

Chu (楚) Status: Eliminated

But the story only goes downhill from here for Helu. Yue (越), seeing that the Wu heartland was poorly defended during the campaign, launched an invasion against its Northern neighbor. Helu’s brother then took advantage of this turmoil to usurp the throne for himself. The Chu king had by this point fled to Qin, and begged for military aid from that kingdom. Helu was forced to quickly declare himself hegemon in the Chu capital before rushing home to crush the threats. As he was retreating, the Qin (秦) army showed up and ambushed them. Then, as the Wu forces fled east with their tails between their legs, the Chu king was reinstated.

You might be wondering, "Why would the Qin help the Chu? Aren't they rivals?" This is true, but the Qin rulers realized that if the Wu army consolidated power, they'd become an even bigger threat than the Chu. By keeping a weakened Chu alive, Qin could secure temporary peace on its southern border, making the rescue worthwhile.

Chu (楚) Status: Revived

Helu’s status as a hegemon is disputed. On the one hand, he had, against the odds, conquered one of the most powerful kingdoms in all of China, a move that, if maintained, would undoubtedly have made him a hegemon. On the other hand, Helu barely had time to enjoy his new conquests before he had to abandon them.

So I say we compromise! Why don’t we declare him a semi-hegemon? Because he was the undisputed hegemon for a very short period of time, he should be considered 50% of one!

You’re probably wondering right now: “Why do all these characters have mouths at the top half of their heads?” The answer, my dear reader, is that… I honestly just suck at drawing speech bubbles.

Wu (吴) is the yellow kingdom to the North, and Yue (越) is the red one to the south.

King Goujian of Yue (ruled 496-464 BC)

King Helu of Wu would spend the rest of his reign trying to rebuild that fleeting empire. In doing so, he exhausted his own forces, and often placed himself in mortal danger. Fate would finally catch up to him in one such expedition against Yue. As he, mounted atop his royal stallion, led his army into battle, an enemy arrow struck him in the toe, causing a lethal infection.

On his deathbed, Helu beseeched his son, Fuchai (夫差), to “Never Forget Yue!” The king of Yue, Goujian, (越王勾践) was oblivious to the tragedy about to befall him.

Rather than continuing his father’s destructive and exhausting campaigns abroad, King Fuchai of Wu spent the first three years of his reign rebuilding his nation’s strength. Then, when the King of Yue made the inexplicable decision to launch an attack against him, Fuchai annihilated that entire force, and captured Goujian.

Yue (越) Status: Eliminated

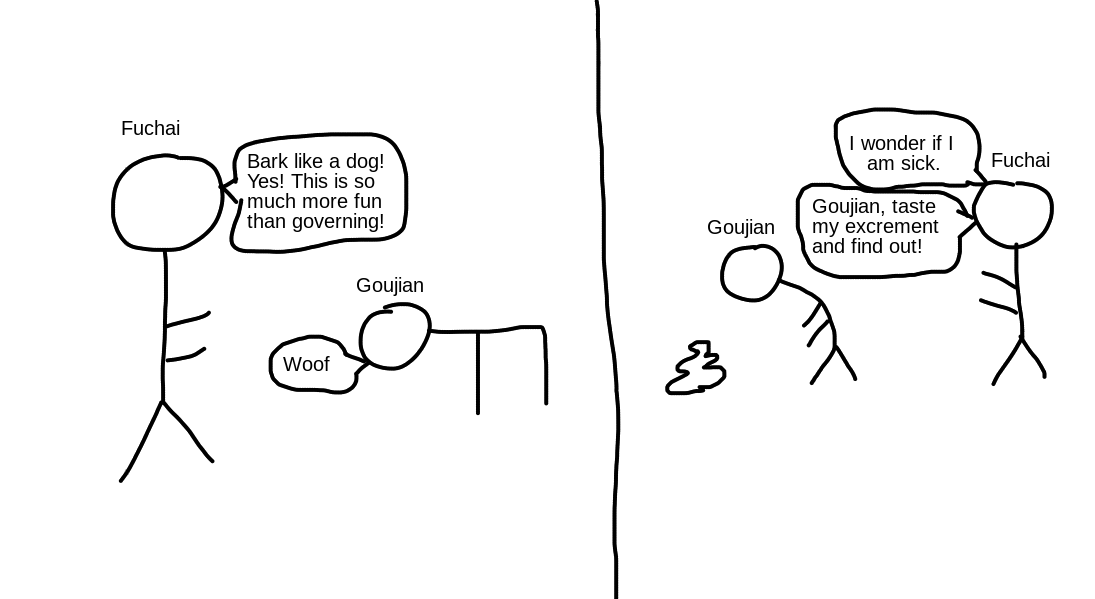

You’d think that Fuchai, having captured his sworn rival, would have killed him. But no—he wanted to utterly and completely humiliate him.

Fuchai humiliated his new captive in every way known to man. But after three years of this, he started getting tired of having a middle-aged, definitely insane idiot as his personal slave. So, he set Goujian free and sent him back home, where he could be the crazy king of his weak and irrelevant kingdom. “What could go wrong,” Fuchai thought to himself…

Yue (越) Status: Revived (dun dun duuuuun!)

What’s about to happen next is one of the greatest comeback stories of all time. Goujian’s humiliation left a lasting mark on his heart, and he swore revenge on his captor. Every night, rather than sleeping in the royal bedroom, he would lie down on a pile of sticks, so as to not forget the humiliation of his captivity. And each morning, when he opened his eyes, he would lick the raw liver hanging above his bed, and the bitter bile would remind him of his desire for revenge.

In 482 BC, nearly a decade after Goujian’s release, Fuchai wanted to be hegemon so badly that he took his entire army north and invaded Qi (齐), leaving virtually nobody to defend his own kingdom. Goujian, sensing an opportunity, invaded Wu, murdered Fuchai’s son, and forced Wu to sue for peace on unfavorable terms.

A few years after that, Goujian attacked Wu again, besieging its capital. Weakened from its many inconclusive conflicts abroad, Wu was in no position to protect itself. Fuchai, probably regretting his naive decision to set Goujian free all those years ago, committed suicide on a nearby hill.

Wu (吴) Status: Eliminated

Goujian became the final hegemon of the Spring and Autumn Period. The conquest of Wu would prove to be the final major confrontation in the Spring and Autumn Period.

Goujian’s hegemony is debated. Despite being quite powerful, he never did expand his kingdom beyond that sliver of land east of Chu (楚), and south of Qi (齐) during his lifetime.

China remains divided. Nobody has won yet. And the worst wars are yet to come.

I would show a cool map of what China looks like now, but I think it’s better to wait till the next post. So instead, let’s check in on our good friend, the Zhou Dynasty.

TO BE CONTINUED…

Bonus: 753 BC in Italy, just 18 years after the fall of the Western Zhou Dynasty.

Leave a Comment

Comments