Warring States Period - Part 1

Let’s begin from where we left off last time, with the death of King Goujian of Yue (越王勾践). By the later years of the Spring and Autumn Period, most small kingdoms were vanquished by their larger neighbors. Besides the shock and awe campaign that King Helu had waged against the Chu, there were no significant instances of a larger kingdom losing a large amount of territory to another kingdom. An uneasy calm settled over China, even as rival rulers jostled for power in an increasingly fragmented nation.

This situation lasted for an extensive period of… 9 years.

Just as a reminder, this map shows what China looked like before the conquest of Wu by Yue. The only powerful kingdoms remaining are Qin (秦) in the West, Chu (楚) in the South, Jin (晋) in the Northwest, Qi (齐) in the East, Yan (燕) in the Northeast, and Yue (越) in the Southeast. Of the original contenders, Song (宋) in the Yellow River Valley is still around, albeit in a significantly weakened state. Zhou (周) is technically still the ruler of all of China, but it has become quite irrelevant, just like the other small kingdoms in that region. By this point, they essentially leaned whichever way the wind blew, and lost virtually all autonomy to the larger states surrounding them.

The Dissolution of Jin (455-403 BC)

During the early years of the Spring and Autumn Period, Jin (晋) was the pre-eminent power in China under its powerful ruler, Duke Wen (晋文公). But by the late Spring and Autumn period, it had become just as fragmented as the whole of China was. Trusted advisors of the rulers were given their own fiefs, which were passed down from generation to generation (my, oh my, doesn’t this sound familiar!). By the fifth century BC, central control of the kingdom had diminished drastically, and power fell into the hands of powerful local fief-holders. The four most powerful were as follows:

The Earl of Zhi (智伯)

The Viscount of Zhao (赵子)

The Viscount of Wei (魏子)

The Viscount of Han (韩子)

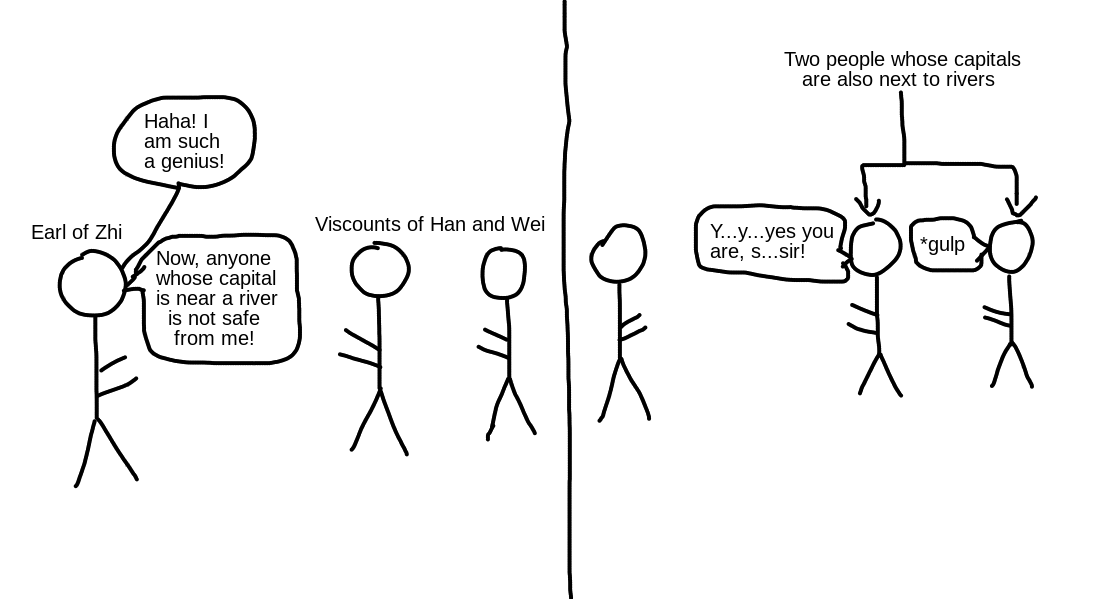

Without the strength of the Duke of Jin keeping these nobles in check, they began to jostle with each other for power. By 453 BC, the most powerful of the four patriarchs, the Earl of Zhi, was demanding tribute from the other three.

The Viscount of Zhao, the most obstinate of the three rulers, refused to submit. So, Zhi raised an army and, with Wei and Han, encircled Zhao’s base of operations, Jinyang (晋阳).

Jinyang’s garrison defended their home ferociously, and the alliance could not break through the city walls. The nearby river also proved a useful line of defense. So the Earl of Zhi came up with a plan: if he could divert the river’s waters toward Jinyang, and build a barricade to prevent the water from inundating his own camp, then he could flood the city!

The earl, absorbed by his own hubris, forgot that his allies’ capitals were also next to rivers. This insensible comment would have a ruinous effect on his campaign.

The three armies put their plan into action. The floodwaters roared toward the Zhao capital, with the three separate allied encampments protected by carefully built barricades. As night was about to fall, the Viscounts of Han and Wei climbed onto a nearby hill to get a better look at the situation. The sight filled them with a sense of dread. If this could be done to Zhao, why wouldn’t Zhi then turn this same tactic against them?

As nightfall came, the besieged Zhao, in desperation, sent an envoy to Han and Wei, begging them for help. The envoy reminded the Viscounts that their capitals were next to rivers, and thus were just as vulnerable as Jinyang to a Zhi attack. Convinced by the envoy’s reasoning, and already fearing that possibility, the two Viscounts accepted a secret pact with Zhao. As the Earl of Zhi slept soundly in his tent, engineers from the three Viscounts’ armies snuck down to the river, and quickly eradicated the barricades protecting the Zhi camp. The water, which seemed like a monolithic tower bearing down on the besiegers even from afar, suddenly reversed direction, rushing down upon the Earl’s forces.

Zhao, Wei, and Han then simultaneously attacked the Earl’s disoriented and fleeing men. In the bloody melee that ensued, the Earl himself was felled, and his men either surrendered or were hacked to pieces.

Wei (魏), Zhao (赵), and Han (韩) then carved up the territory of the Zhi and declared themselves Marquesses, relegating the Duke of Jin into a ceremonial figurehead. In 376 BC, these three kingdoms divided the remaining territories of Jin among themselves. This event, known historically as the three families splitting Jin (三家分晋), marked the beginning of the Warring States Period (战国时期).

Jin (晋) Status: Eliminated

New Contenders Have Entered the Field: Han (韩), Zhao (赵), Wei (魏)!

Here’s what China looks like now.

8 major contenders remain able to dominate over China. They are, from west to east, as follows: Qin (秦), Zhao (赵), Wei (魏), Han (韩), Chu (楚), Yan (燕), Qi (齐), and Yue (越). Each kingdom will have an opportunity to grow powerful, so the contest to unify China will come down to who can grasp onto that opportunity till the end.

Sun Bin and Pang Juan

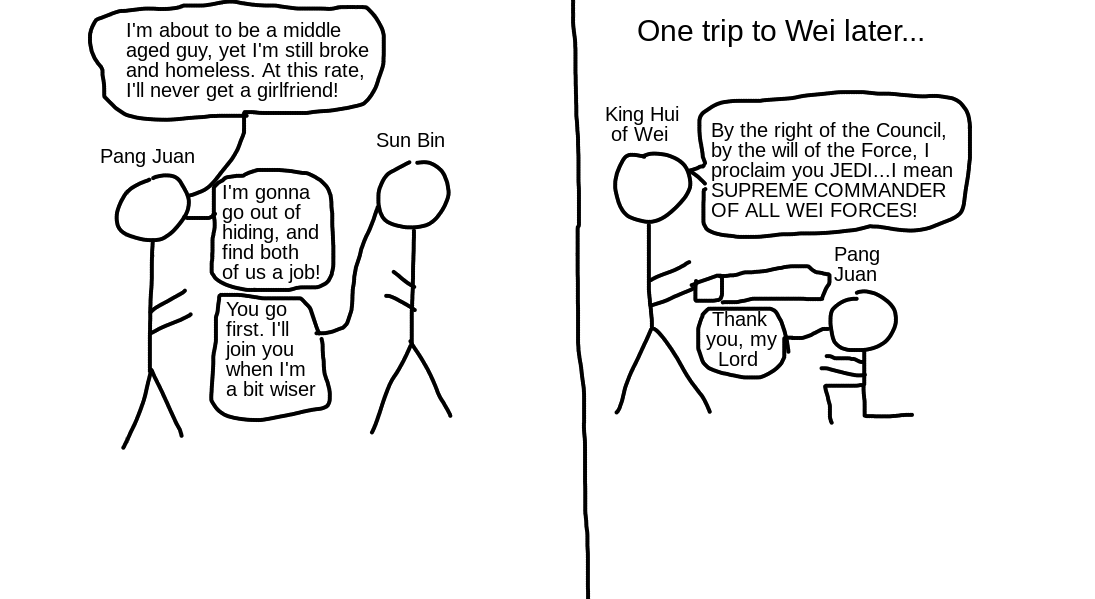

In the early years of the Warring States Period, there was a mysterious recluse named Gui Guzi (鬼谷子). Having isolated himself from politics and warfare, he would have been utterly irrelevant if it had not been for the achievements of his two star students: Sun Bin (孙膑) and Pang Juan (庞涓).

As Gui Guzi taught these two men the ins and outs of warfare, the situation in China was changing rapidly. In the fertile eastern lands of Qi, the House of Jiang (姜), descended from Jiang Ziya himself, declined in power as the House of Tian (田) grew in strength. In 379 BC, the death of the childless Duke Kang of Qi left the door open for the Tian patriarch to openly declare himself the new duke. At around the same time, the Kingdom of Wei, sandwiched between Han and Zhao, was nearly annihilated by its former allies. Its nonsensical borders (Check the map. Wei is literally chopped in half) made it an easy target. In the end, it was Han and Zhao’s inability to decide who should get what that saved Wei from being conquered entirely. After this crisis, Wei elected a new Marquess, who reorganized the kingdom's borders and strengthened the military. In subsequent years, Qi and Wei would bestow upon their rulers the title of “king.” The first king of Qi was King Wei (齐威王) (378-320 BC), and the first king of Wei was King Hui (魏惠王) (369-319 BC). They, along with Chu, now considered themselves coequal with the Zhou king himself. And their lands could now officially be designated as kingdoms.

Two things of note. Firstly, in the previous post, it was suggested that the story of the bird call (一鸣惊人. Does this jog your memory?) jolted King Zhuang of Chu out of his torpor. However, most historians now believe that it was King Wei of Qi who was on the receiving end of that tale.

Secondly, I called almost every state during this period “kingdoms.” That is a misnomer. Technically, most were duchies throughout the Spring and Autumn Period, and only during the Warring States Period did the remaining ones become kingdoms. But personally, I don’t find these distinctions to be that important.

For the next quarter-century, Wei and Qi would be similarly powerful, and would compete for preeminence in the country. Their power struggle would closely follow the paths of Pang Juan and Sun Bin.

Phew! The boring history rant is over!

Under Pang Juan’s deft leadership, Wei repelled its foes and became a powerhouse to be reckoned with. For a time, King Hui of Wei was the most widely feared monarch in all of China.

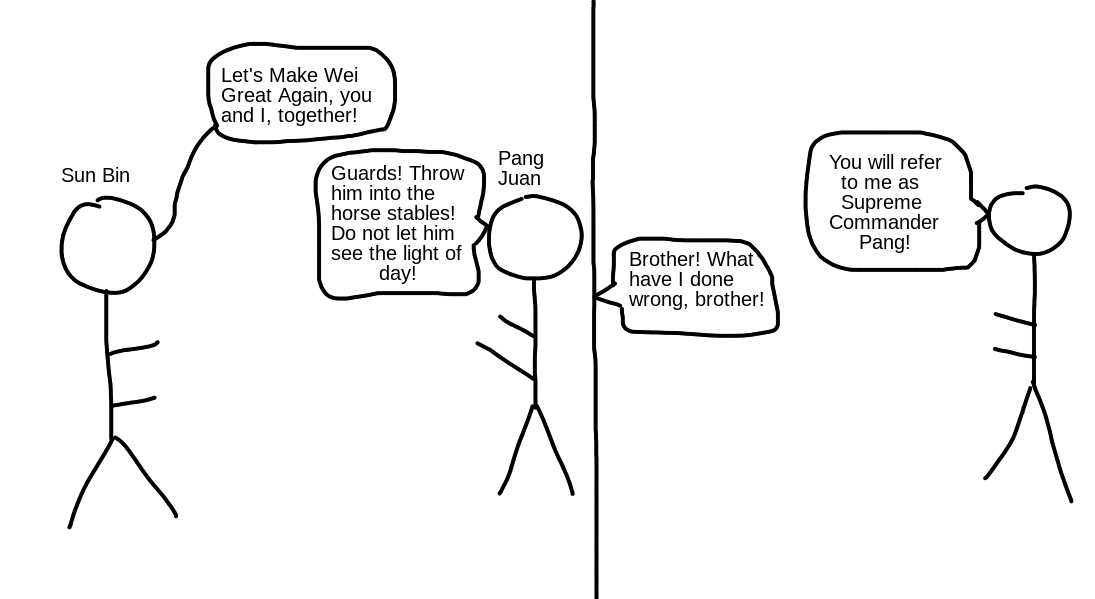

A few years later, Sun Bin went to Wei as well, hoping to land a posh job through his powerful and influential friend. But as the saying goes: “Power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” Not even the deepest friendship can break that maxim.

Realizing that Sun Bin, having studied under Gui Guzi for longer, was likely more skilled in warfare than he was, Pang Juan moved to protect his prestigious post. Sun Bin was jailed. But before executing him, Pang hoped to extract his excess knowledge. So he ordered Sun to create an Art of War, Sun Bin edition. To further…convince Sun, Pang brutally tortured his old friend, digging out his kneecaps and forcing him to crawl in agony through the streets.

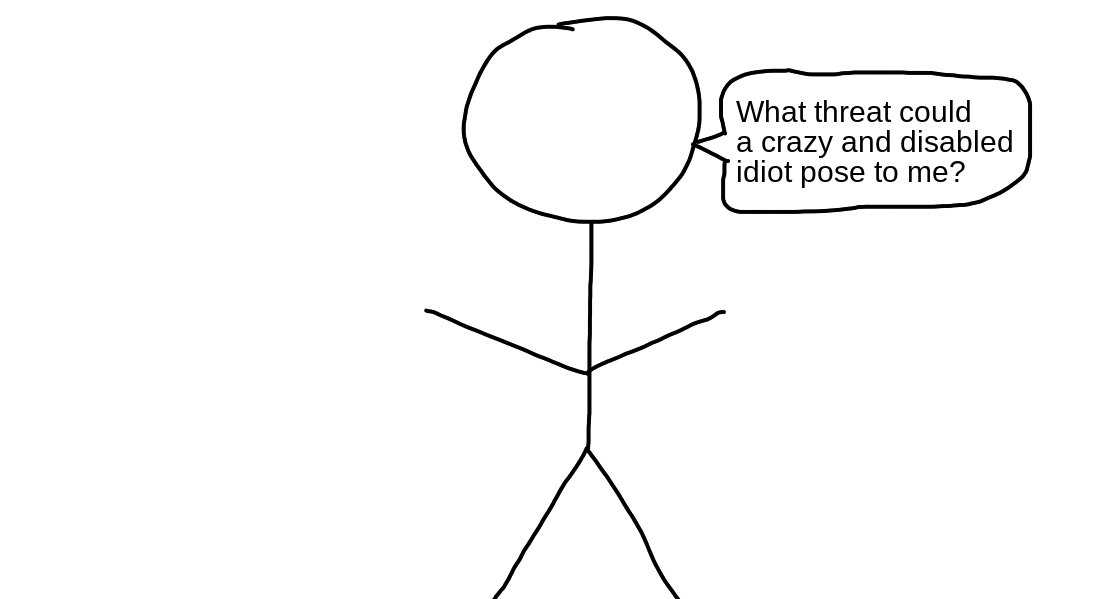

But Sun was resilient and intelligent. He eventually came to realize that if he submitted to the agony and put his knowledge onto paper, then his former friend would have no reason to keep him alive. So, he began to fake his own insanity. When Pang threw him into the horse stables, he began eating the manure and loudly declaring its tastiness! Seeing this, Pang gave up, and the torture stopped. But Pang never killed Sun. It was not necessary to eliminate an insane man who couldn’t even walk. “What threat could he possibly pose?” Pang thought to himself. “When was the last time a guy who liked eating poop turned out to be an actual threat?” (for all those who read the previous blog post, this is called…a callback!)

Some years later, an envoy from Qi was sent to Wei to negotiate some unimportant treaty. As Pang was giving this envoy a tour of the Wei capital, Daliang (大梁), he thought it would be funny to show him his crazy, dung-eating prisoner. So Pang took the envoy to the stables.

The envoy, rather than being horrified or disgusted, studied this abnormal specimen of a man. Staring deep into his eyes, he realized something Pang never did: Sun's insanity was an act. What’s more, he could tell that Sun’s brainpower was far from ordinary.

Returning home, the envoy created a plan to sneak Sun out of Wei. The plan succeeded, largely because Pang’s thought process was…

Sun Bin in Qi

Smuggled east to Qi (齐), Sun Bin found a leader willing to accept his talents in King Wei of Qi (齐威王). Soon, he became the kingdom’s top military advisor. Because Sun was unable to walk or ride a horse, the king even ordered a personal wheelchair to be built for him, so he could personally oversee battles and, if the opportunity allowed, witness the downfall of his enemy, Pang Juan.

In 354 BC, a massive Wei army moved North into Zhao (赵), hoping to conquer this sizeable kingdom as the first step to unifying all of China. Who was at the head of this army?

Pang Juan, of course!

The unassailable Wei army quickly placed the Zhao capital, Handan, (邯郸) under siege. In desperation, the Marquess of Zhao sent out envoys to the other kingdoms begging for military assistance. King Wei of Qi, hoping to maintain the balance of power in central China, responded by sending out an army under General Tian Ji (田忌) and advisor Sun Bin to rescue Zhao. Tian, an efficient commander, quickly assembled his army and sped west.

Qi’s military was no pushover, but there was no guarantee that it would beat Pang’s. Thus, Sun Bin suggested an alternative to facing it head-on. Why don’t we besiege the Wei capital, Daliang (大梁), he mused in a meeting with Tian. This way, Pang will be forced to return and rescue it, and the siege of Handan will be lifted!

Tian adopted this idea immediately.

Tian’s army lumbered toward the Wei capital, but a forward detachment was sent out in order to reach Daliang more quickly and to make their presence known. King Hui of Wei, having sent the bulk of his army out with Pang Juan to besiege Zhao, panicked. He repeatedly sent messengers to Pang, ordering him to return and relieve the city.

Pang did not want to lift his siege, believing Handan would fall within days. So he decided to leave the bulk of his force to continue the fight, and leading a light cavalry contingent, rushed back to dispose of what he thought was a meager force. However, far from meeting a tiny contingent, he was intercepted by the bulk of the Qi army at Guiling (桂陵). Though a ferocious force, the contingent was wiped out by its much larger opponent. Pang himself barely escaped the carnage alive. Now recognizing the magnitude of the threat, he recalled his troops from Zhao. With Handan relieved, Tian Ji ordered his men home without any further confrontations.

If Sun Bin could have seen his former friend fleeing the field, he probably would have smiled to himself.

This stratagem of launching a diversionary attack to force your enemy to retreat even has its own name: 围魏救赵, or surrounding Wei to rescue Zhao. This might be a good strategy for all you Hearts of Iron players out there!

But Pang Juan is still alive! So of course, his mischief continued!

Pang Juan invaded Han. Tian Ji and Sun Bin responded by besieging Daliang again, forcing its king to recall Pang Juan with haste. But this time, Sun Bin would not let him escape. Before the expedition had even set out, Sun had calculated Pang’s quickest path of retreat from Han. He realized that the journey would invariably take him through a narrow gorge at a place called Maling (马陵), with high cliffs on both sides. So he advised Tian Ji to station a squad of archers on the cliffs to ambush Pang’s troops, a suggestion which Tian gladly accepted.

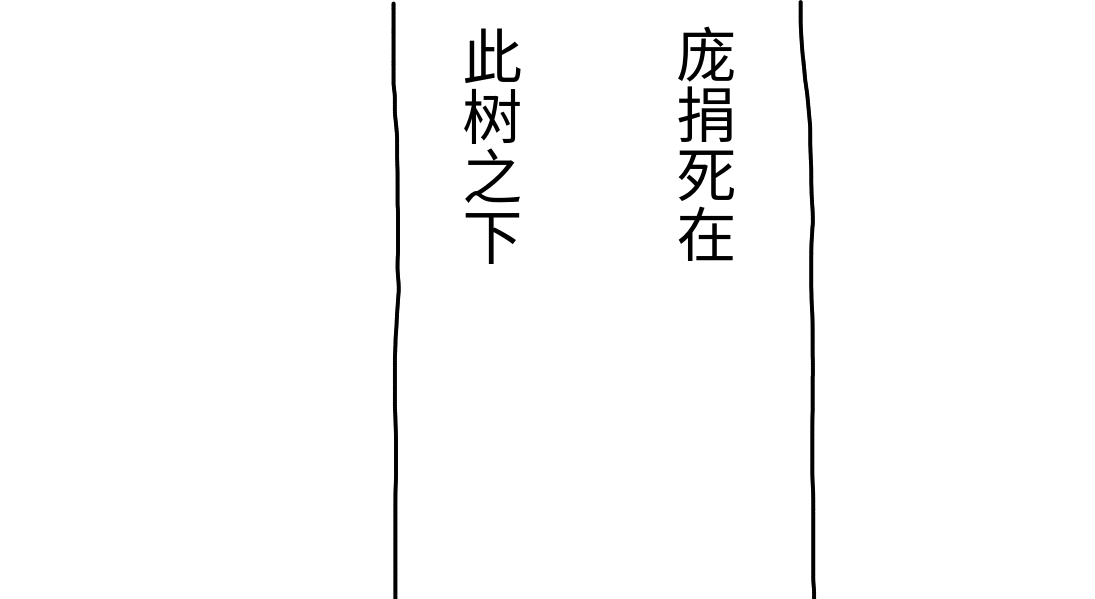

Pang’s retreat took many days, but being in a hurry, he rarely allowed his troops any rest. It was late in the night when they reached the narrow gorge, the darkness concealing the archers on the steep cliffs. Halfway through the gorge, Pang noticed a lonely tree, casting no shadow on this moonless night.

He raised a lantern to the tree and found eight words carved into its trunk.

“Pang Juan will die beneath this tree.”

Suddenly, a flurry of arrows rained down upon the entrapped Wei army. The soldiers panicked and trampled each other trying to escape. Sun Bin, seated in his wheelchair, peered over the edge to monitor the situation of the battle. Below, with the dim illumination of the lantern, Sun could see the defeated face of Pang Juan as he raised his sword and slit his own throat.

Within just a few years, Wei went from one of the most powerful states in China to a declining state. Qi was now the preeminent power in the East.

Shang Yang’s Reforms (circ. 350 BC)

Let’s now shift our gaze toward the West. For centuries, the state of Qin was irrelevant in the affairs of the central plains. It spent a lot of time expanding its frontiers westward and southward against nomadic tribes. But in that time, its armies had failed to modernize, and its land was vast and generally uncultivated. Population-wise, Qin way underperformed what its size would suggest. Duke Xiao of Qin (秦孝公) wanted to change that.

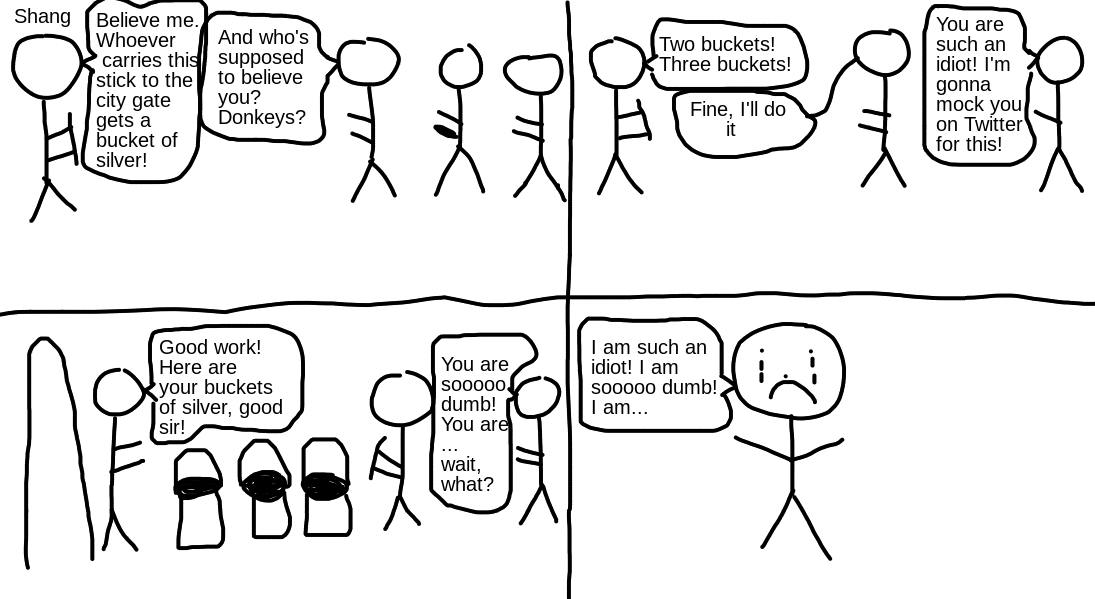

There was once a young, low-level official from Wei named Shang Yang (商鞅). Attracted to Qin by its openness to new talent, Shang got an audience with the Duke himself, allowing him to dazzle Duke Xiao with his vision for the future. Duke Xiao, thoroughly impressed, immediately made him high chancellor.

In this new post, Shang implemented two major reforms to Qin’s system of government. First, he wanted to concentrate power in the hands of the king. Secondly, he wanted to enforce a strict legal code that would severely punish wrongdoing but lavishly reward bravery and obedience.

But before he could do any of this, he needed to restore faith in the Qin government’s word. After all, if people believe that the government will actually do what it promises to, who will abide by the new law code?

After this public display, Shang went about his reforms with the full faith of Qin’s citizenry. Shang wanted a strong monarch who could, through steady governance, guide the nation to greatness (he was China’s Machiavelli). This would require stripping power away from the nobles. So he implemented a new policy by which any peasant could gain land, money, and a noble title through courage and bravery on the battlefield. There was plenty of empty land, after all! As for the existing nobles, those who refused to fight were stripped of their titles. Equality under the law!

And how would bravery on the battlefield be measured? Why, by the number of heads you chopped off, of course! Henceforth, after each battle, all soldiers would carry back the decapitated heads of dead enemy soldiers, and every head was worth a certain amount of gold. This inhumane system turned the Qin army into a band of ferocious, bloodthirsty warriors.

Shang also changed the governing structure of the entire kingdom. Previously, nobles controlled large swathes of land and were essentially governors within their fiefs. Shang Yang reorganized a large amount of territory into provinces and counties, governed by appointed officials rather than hereditary nobility. The nobles hated these reforms, but with the full backing of Duke Xiang, they were passed without major obstruction.

Shang also encouraged foreign citizens to enter the country freely and cultivate the land. These new policies turned Qin from a peripheral state into a force to be reckoned with. And the first country to experience Qin’s reenergized wrath was the declining state of Wei.

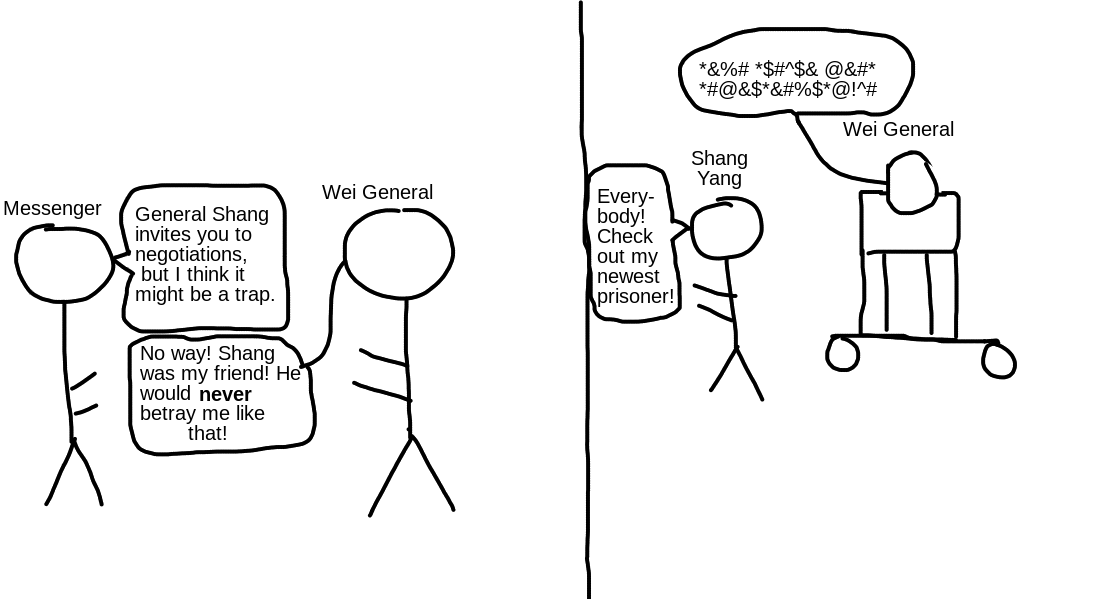

(That thing with wheels is supposed to be a prison cart. Until modern times, prisoners in China would often be transported on what essentially was a tiny jail cell on wheels)

In 341 BC, Shang attacked his former home, and forced it to cede all lands west of the Yellow River to Qin. To put how shocking of a turn this was into context, just a few decades before this, Pang Juan had mused that Wei could single-handedly conquer Qin, but decided against that idea only because Qin’s land was undesirable. Now, Wei was the one forced to cede its fertile territory to Qin.

Furthermore, Shang Yang oversaw the construction of a new capital, Xianyang (咸阳), so that the rulers of Qin could escape the influence of the nobility, which had extensive roots in the old capital. All of these reforms centralized the Qin state, which would declare itself a monarchy within a generation. Its army was now quickly toughening, and with new foreign talent at its head, it would soon become the most proficient in all of China. Immigration transformed areas that were once barren wastelands into a steady source of revenue for Xianyang’s coffers. Qin’s location also meant that its eastern frontier was an impassable mountain range. The only way to get in and out of Qin’s land from that direction was through a single fortress at Hangu Pass (函谷关). If any enemy wanted to attack Qin, they would have to do so through this one near-impassable fortress. Thus, safe behind nature’s walls, Qin expanded southwards, conquering the states of Ba (巴) and Shu (蜀) and expanding its reach into modern-day Sichuan and Chongqing (that’s actually where my parents, and numbing Szechuan peppercorns, originate from!).

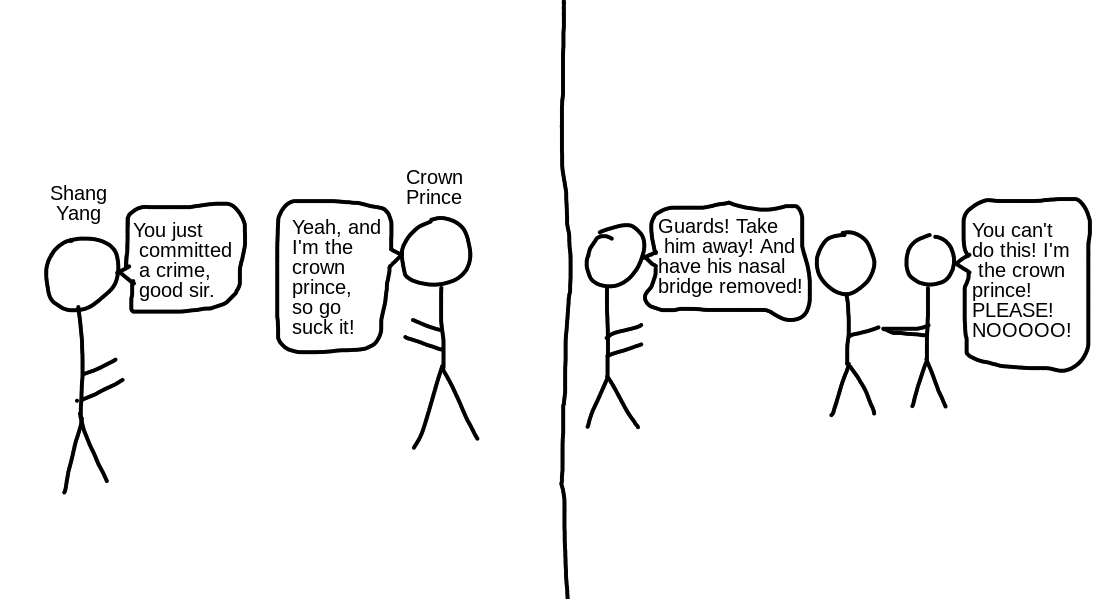

Yet Shang’s reforms did not please everyone, and he made a fatal error when trying to enforce the laws on the crown prince of the state.

Max Facts! King Huiwen likely started off his reign as Duke of Qin, but recognizing that Qin was growing increasingly powerful, he decided the time was right to turn his state into a kingdom. By the end of the 4th century BC, all major states across China would be ruled by kings, but the Zhou king was technically still in charge, because he was still the Son of Heaven…

Duke Xiao allowed these punishments to take place since equal enforcement of the law was a crucial aspect of Shang’s reforms, but he did not strip the punished royal of his position. So when Duke Xiao died in 338 BC and the crown prince took over as King Huiwen of Qin (秦惠文王), Shang Yang was pretty screwed.

Shang Yang attempted to flee the state. One night, he passed a small village and attempted to get shelter for the night. However, the family refused him, afraid they would be punished for allowing a man without proper ID through their front door.

And who implemented this strict ID law, you may ask? Of course, it was Shang Yang himself!

Eventually, Shang was captured, and executed by drawing and quartering. But his reforms lived on, and so did the ascendancy of Qin.

Interlude (Just checking on all the other kingdoms)

By the late 4th century BC, China was filled with states that were declaring themselves monarchies. Chu had gone first, Qi and Wei had gone next, then Qin. Han, Zhao, Yan, and even the small and irrelevant Zhongshan (中山国) would declare themselves kingdoms soon after. Chinese history courses often encourage (AKA force) students to remember the names of the 7 Warring States, (战国七雄) namely Han (韩), Wei (魏), Zhao (赵), Chu (楚), Yan (燕), Qi (齐), and Qin (秦). Here they are on a map, with no other pesky kingdoms to distract you from their glory!

Where is Yue, you may be asking? And why does Qin now occupy the western half of Chu? Those questions, and many others, will be answered soon, in our second installment on the Warring States Period!

TO BE CONTINUED…

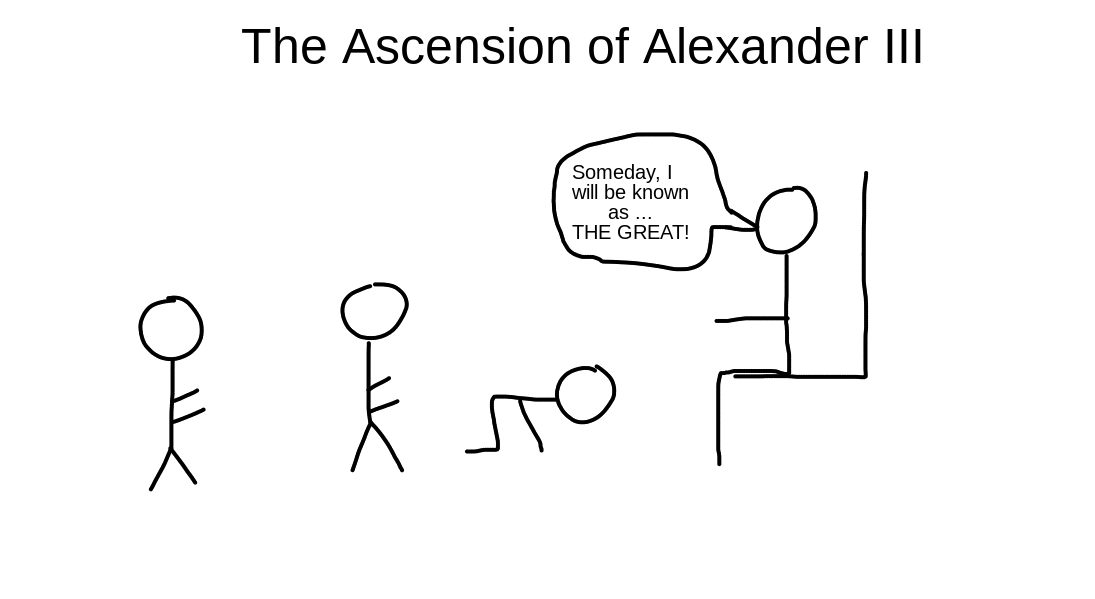

Bonus: As Shang Yang was implementing his reforms in Qin…

336 BC.

Leave a Comment

Comments