Warring States Period - Part 2

Where did we leave off? Oh yeah!

The situation by about 300 BC is a little different from what the map shows. Qin expanded southward, conquering Ba and Shu, while Wei fixed its weird borders. However, what hasn’t changed is that those tiny kingdoms in central China are still irrelevant. So let’s remind ourselves of the seven contenders for the throne of Chinese unification!

There’s Qin (秦), which is on the rise after Shang Yang’s reforms. Wei (魏) is on the decline after Pang Juan’s disastrous defeat at Maling (马凌). Han (韩), arguably the weakest of the great warlords, now precariously balances itself between its neighbors. And then there’s Zhao (赵) and Yan (燕), which are less resource-rich than their neighbors. Chu (楚) is still around, and is widely seen as a bulwark against the rising threat of Qin. Qi (齐) is still just sitting on its eastern territories, getting rich from salt and fish.

Su Qin and Zhang Yi

Max Facts! Ancient sources contend that the teacher of both Su Qin and Zhang Yi was Gui Guzi (鬼谷子), also the mentor of the Sun Bin and Pang Juan pair! As it turns out, he was proficient not just in combat, but also in the art of persuasion.

The Qin kingdom’s rise was unlike any other during this period. In fact, by 300 BC, every other kingdom feared it. Amid this general panic, Su Qin (苏秦) would become the leading advocate for a methodical approach to suppress the Qin Kingdom’s rise.

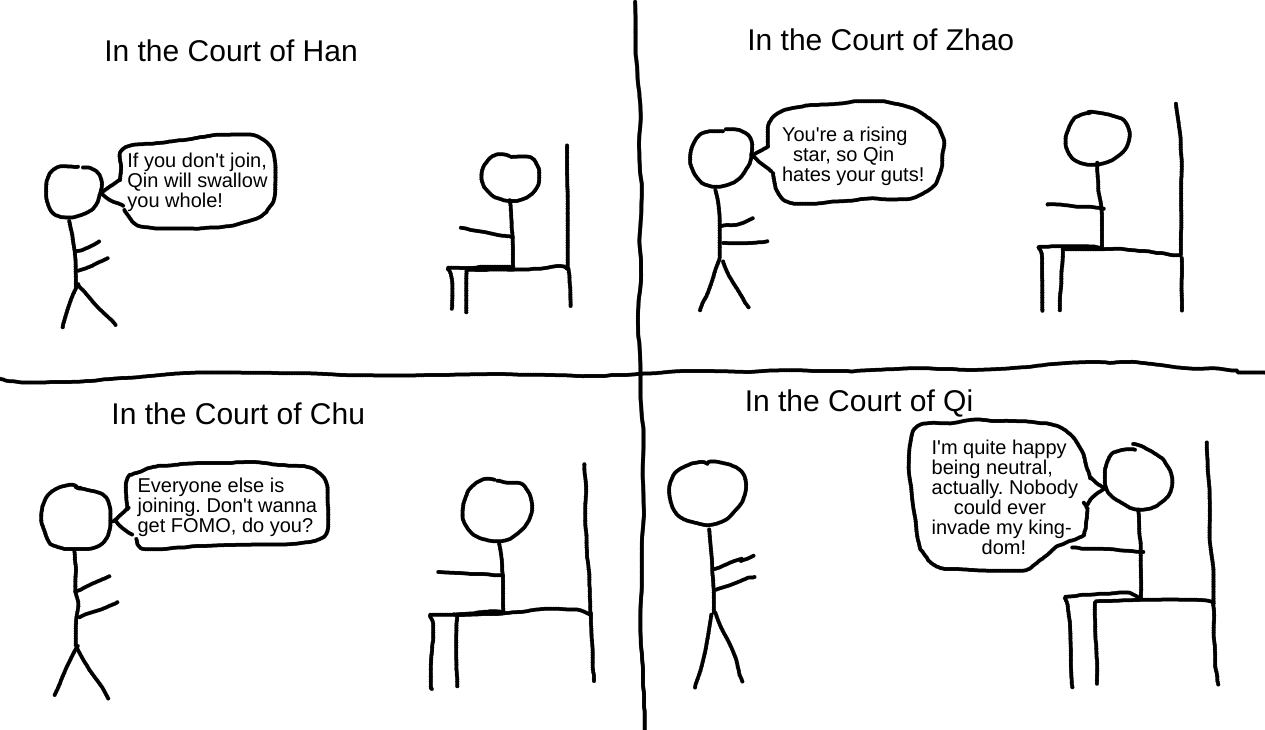

Su began his career as a lowly scholar in the state of Yan, but quickly rose through the ranks by advocating a foreign policy known as the “vertical alliance” (合纵). This policy called for the cooperation of the six great Eastern powers against the rising one in the West. In 334 BC, Su Qin was sent out to convince the other rulers to adopt his proposal and join the alliance.

That last part is called…foreshadowing! Also, I do realize that the thrones are floating. Hopefully, that isn’t too disorienting.

Except for Qi, every other kingdom joined the vertical alliance. Consequently, Su Qin became the most prominent politician in Eastern China. This first vertical alliance halted Qin’s expansion for fifteen years. But mutual defense wasn’t enough for many members. They felt, instead, that an offensive was necessary to eliminate Qin altogether.

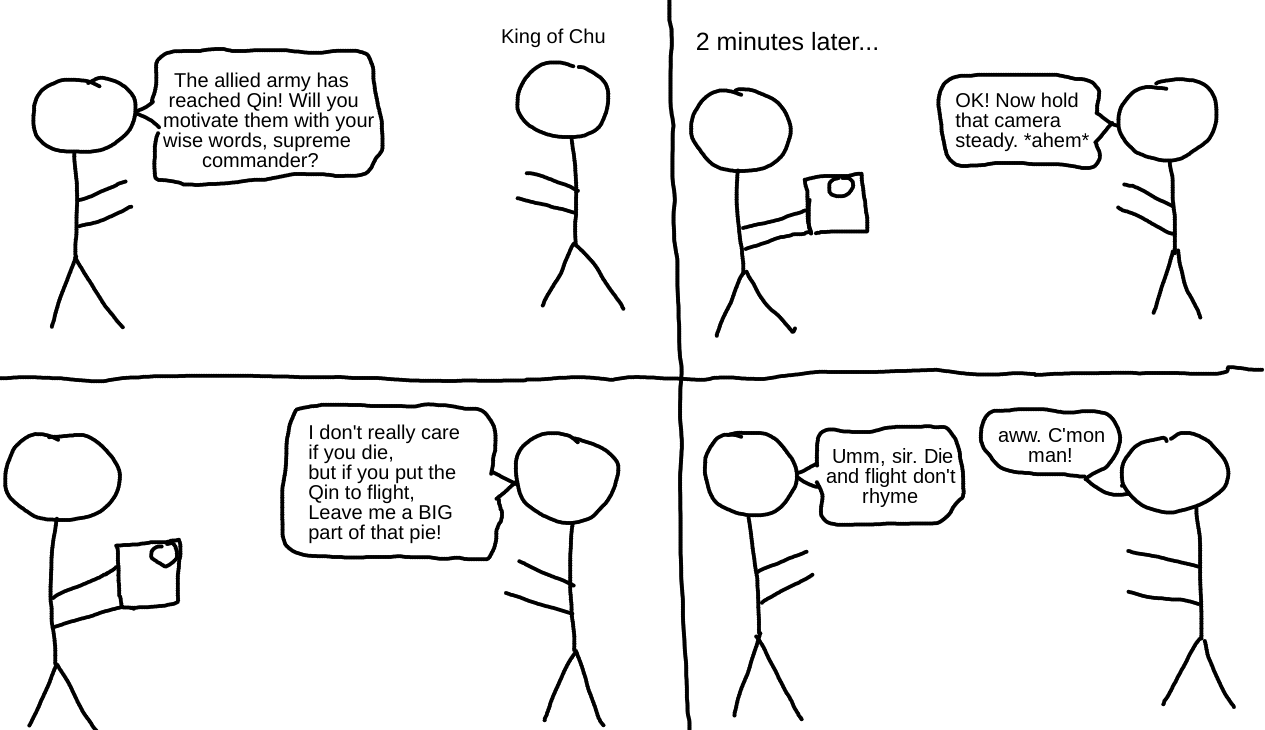

In 318 BC, all the kingdoms of the vertical alliance, this time persuaded by a man named Gonsun Yan (公孙衍), launched an attack against the Qin fortress Hangu Pass. King Kaolie of Chu (楚考烈王) was supposed to be the leader of this alliance. But he was not exactly the most… avid commander the alliance could have picked.

Only the kingdoms of Han, Zhao, and Wei ordered troops into the field, but they were quickly driven back, facing tremendous casualty numbers of 82,000. This shocking defeat put an end to the first concerted effort at “vertical alliance,” and although the idea would be revived each time the Qin got a little too uppity, none would be nearly as long-lasting as the first.

As the vertical alliance reeled from the defeat, Qin sought to sow further divisions. Divide and conquer was the motto. And there was one man who embodied this ideology more than any other.

His name? Zhang Yi (张仪).

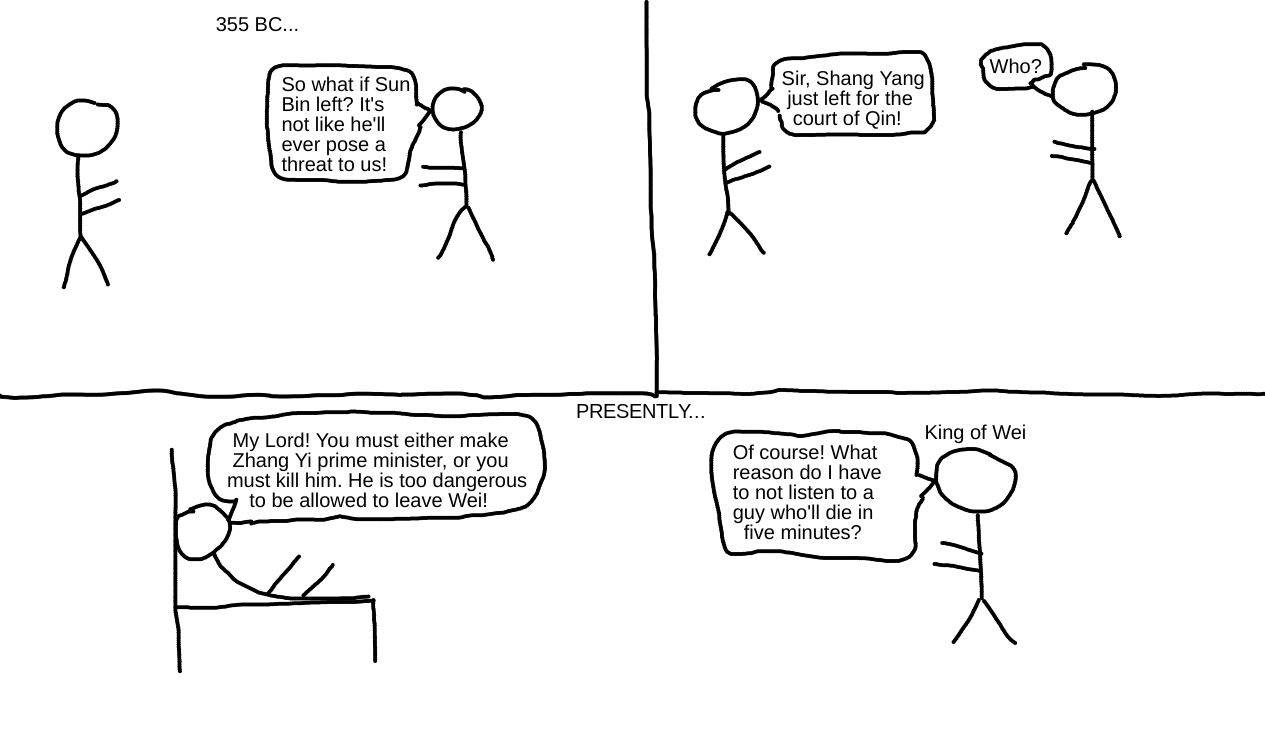

His place of birth? Wei, of course.

Zhang Yi was born in Wei. But after being repeatedly sidelined by its king, he fled to Qin, and convinced its ruler, King Huiwen, to make him an official within his court. And just like Shang Yang, who had also been humiliated by his former home, Zhang Yi recommended that Qin immediately attack Wei.

However, Zhang was less famous for his vengeance against Wei than for his advocacy of the “horizontal alliance” system (连横). The basic idea was this: “If you hate all those other pesky kingdoms who do nothing but bicker, be friends with Qin instead! And you two can be powerful together!”

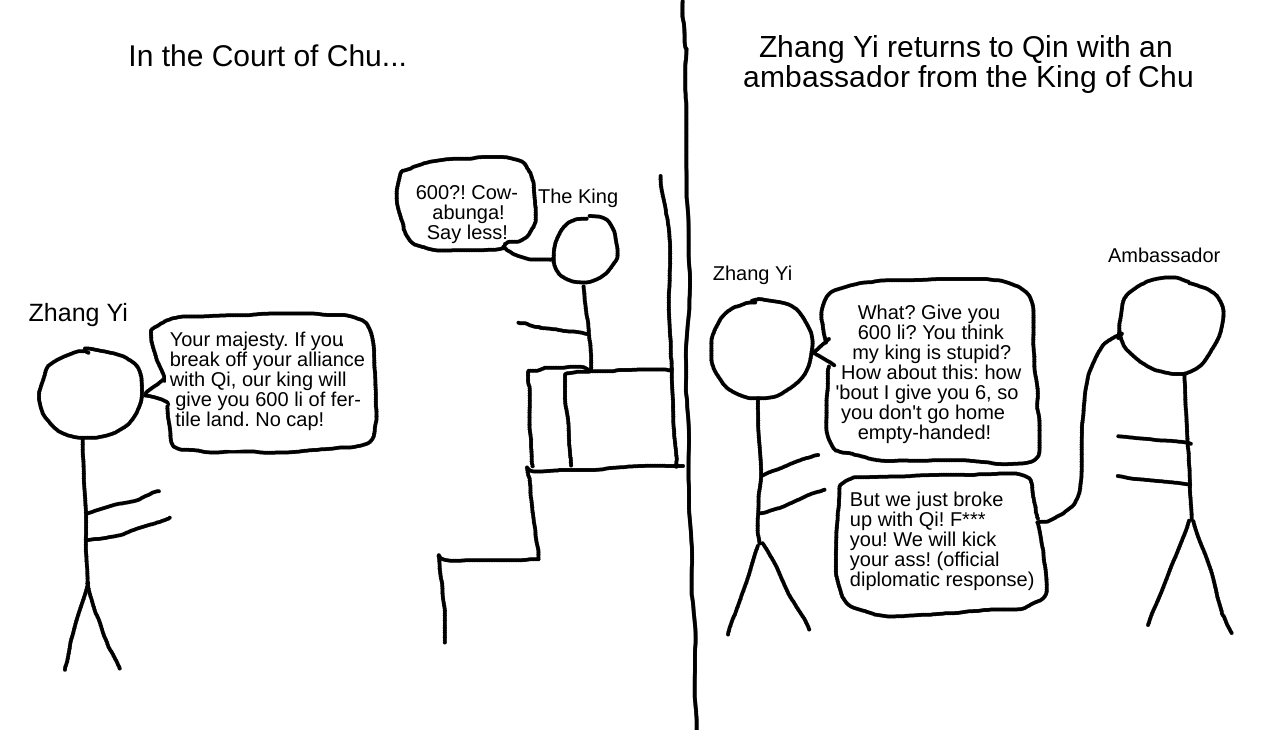

In 313 BC, Zhang tricked King Huai of Chu (楚怀王) into ending his alliance with Qi. When King Huai realized Zhang’s deceit, he ordered an invasion of Qin, only to be attacked simultaneously from east and west (turns out, Qi was not a huge fan of their ally randomly breaking off relations). Rather than gaining territory, Chu was forced to cede two cities to its western neighbor, and gained a new enemy on its northeastern flank.

Despite these setbacks, the Chu remained a great power and a strong rival of the Qin. Its position was bolstered in 306 BC (dates vary) when it conquered Yue, following that kingdom’s ill-advised offensive against Chu from the east. The situation was still very fluid, and despite its growing power, thanks to Zhang Yi’s “horizontal alliance” system, Qin's dominance was far from guaranteed.

But while China’s attention was directed solely at the west, a new power would emerge in the North.

The Ascendancy of Zhao

The kingdom of Zhao (赵国) was never quite powerful. If you read the last installment of this series, you might remember that it appeared only as the victim of an invasion by Pang Juan. So, how did Zhao go from a weak and vulnerable Northern polity into the powerhouse of the former Jin breakaway states? The story begins with King Wuling of Zhao (赵武灵王).

In 307 BC, King Wuling ordered an invasion of the tiny state of Zhongshan (中山). Zhongshan was a nomadic kingdom with an underdeveloped economy and a small military. So it came as a complete shock when this happened:

The Zhongshan army was not as large, but it was more maneuverable, and their archers gave them a definitive advantage. Zhao’s defeat convinced King Wuling to initiate major reforms, in a program known as “Hufu Qishe” (胡服骑射). The basic idea was: if we can’t beat ‘em, copy ‘em.

The reforms generated quite an uproar among the Zhao nobility. For one, the reforms called for the imitation of nomadic dress. “We have to get rid of the long ceremonial battle robes that prevent us from even running in battle?” thought the nobles. “Terrible! Civilized men must wear man-dresses!” Another point of contention was the growing emphasis on archers. “Blasphemy!” thought the nobles. “A truly civilized army uses only short-range weapons! That is the Chinese tradition!”

But King Wuling rammed these reforms through anyway. Soon, he would be vindicated for his decision. The strengthened Zhao army used its newfound military prowess to conquer Zhongshan and other nomadic groups, thus absorbing proficient cavalry into its army. With this, King Wuling became the undisputed hegemon of the North. Satisfied with his work, the aging king abdicated, and handed to his son, King Huiwen, a powerful, ascendant kingdom. What could go wrong?

Just four years after King Wuling’s abdication, King Huiwen, fearing his father’s continued influence in politics, had him starved to death in his palace. But despite the death of a valiant ruler, Zhao’s ascendancy continued. The triangle of states that now dominated China were Qin (秦) in the west, Zhao (赵) in the North, and Qi (齐) in the east. Who will come out on top?

The Decline of Qi

Following the death of the wise King Xuan of Qi (齐宣王) in 301 BC, his ambitious son King Min of Qi (齐湣王) ascended. From the very start, King Min desired to become the ruler of all China. To achieve that goal, he launched endless military campaigns against his neighbors, driving back Zhao and Chu forces and even participating in an alliance that defeated Qin and broke through Hangu Pass!

But he failed to capitalize on these victories, and never acted to permanently weaken his enemies.

However, despite his military successes, King Min did not have a knack for civil negotiations. As depicted above, his fickleness caused not only the king of Qin, but even his erstwhile allies to turn their backs on him. King Min’s hubris would not go unpunished.

In 286 BC, King Min attacked Song, a once-wealthy kingdom that was now essentially a buffer state. The kingdom fell quickly. Yet the move was extremely rash. You see, there was an unspoken rule at this time that nobody would conquer Song, because the first one to do so would draw the ire of the other kingdoms. But King Min didn’t care. His army was all-powerful, and nobody could possibly defeat it, right?

(The above image is a fabrication of the author. These leaders did not physically meet.)

In response to the blatant violation of international norms, a six-nation alliance, led by General Yue Yi (乐毅) from Yan, launched a joint offensive into Qi. Lacking the natural barriers that Qin did, and exhausted by continuous foreign conquests, King Min of Qi faced setback after setback, gradually losing the support of his court and the people. In 284 BC, the king was ejected from his capital, Linzi (临淄), by the invading forces, and soon afterward, he was killed in flight (accounts vary). Every member of the alliance except the vengeful Yan withdrew after collecting their share of the spoils of war. By that point, 68 out of the 70 cities formerly held by Qi had fallen into enemy hands.

But Yue Yi would not stop until the two remaining cities, Jimo (即墨) and Ju (莒), were out of the House of Tian’s hands. Theoretically, it should have been quite easy for Yan to break these cities’ defenses, as they had done to numerous other fortresses. But for reasons still unclear to historians today, these twin sieges dragged on for years without progress.

Max Facts! Some historians contend that General Yue Yi was purposefully holding back his troops because he wanted to remain useful to Yan. This may seem quite unreasonable, but considering the number of times monarchs in Ancient China executed highly qualified generals for fear of revolt, there is reason to accept this hypothesis’s validity.

While Yue Yi was out in the field doing…nothing, the King of Yan was growing impatient. “If he won’t break into those cities, I’ll order somebody else to!” he thought. And just like that, the careful Yue Yi was replaced by a much more…careless general.

Seeing this change, the defender of Jimo, Tian Dan (田单), smelled an opportunity. He recognized that the new general was brash and violent. He would use this to his advantage.

Tian Dan spread rumours that the defenders of the city were so cowardly that if the Yan army committed a bunch of public atrocities before the city gates, the people would surrender out of fear. However, these atrocities had the exact opposite effect. It angered the citizenry to the core, and instilled a deadly determination in their hearts. Following this morale boost, Tian Dan hired hundreds of warriors and dressed them up as heavenly soldiers. He then covered a few thousand bulls in colorful drapery and tied knives to their horns. The night of his planned counterattack, Tian Dan sent an envoy to the enemy camp with the keys to the city, claiming they were about to surrender. The Yan army celebrated through the evening, and many soldiers returned to their bunks inebriated.

When the sounds of celebration finally died down, and the empty night brought a moment of quietude, Tian Dan assembled his mixed army before the city gates, and executed his plan. In an instant, thousands of ox tails were set alight, and the frightened bulls rammed into the Yan camp. Blinded by the night and remnants of sleep, the Yan soldiers believed they were under attack from heavenly beasts, and panic ensued. The “heavenly soldiers” followed closely behind. While the Yan army still vastly outnumbered their foes, half of them were too busy wetting themselves out of fear to even pick up a weapon. They fled, losing all semblance of cohesion. Thousands were slaughtered or trampled underfoot. The rest fled through the night, never once turning their head or trying to fight. Other conquered cities, hearing the news, revolted against the newly appointed Yan governors. Soon, all seventy cities of Qi were back in the hands of the House of Tian. Yan quickly sued for peace.

While this was one of the greatest comeback stories in the Warring States Period, Qi’s economy and manpower were irrevocably damaged by this incident. Though it would continue to exist, it could no longer claim to be the hegemon of the East.

Chu Faces a Grave Setback

While Qi was figuring out its own national crisis, the great southern bastion, Chu, faced a calamity of its own. By 280 BC, under the misrule of King Qingxiang (楚顷襄王), Chu had grown increasingly weak and decadent. Meanwhile, the new king of Qin, King Zhaoxiang (秦昭襄王), had intentions to expand his own territory at Chu’s expense. To this end, he entrusted command of the armed forces to Bai Qi, an experienced and tested general (白起). Bai would prove to be one of the greatest military commanders in Chinese history.

In 278 BC, Bai Qi was ordered to invade Chu from the Northwest. At first, Bai was largely successful in his campaign, conquering many cities in a short period. But his army was halted at the gates of the city of Yan (焉) (not the kingdom), bogged down by a lengthy siege. If the city didn’t fall soon, the enemy would have time to gather troops around their capital, Ying (郢), and possibly launch a counterattack. What would Bai Qi do?

Water warfare! By redirecting the waters of a nearby river, Bai flooded the city of Yan, brutally drowning hundreds of thousands of civilians. When the water finally receded, and the victorious Qin army entered the city gates, they were instantly met with the terrible stench of rotting human flesh.

The last great fortress between Bai’s forces and the capital had fallen. But to capture Ying itself would be no easy task. It had, after all, been the Chu capital for centuries, and therefore had been heavily reinforced over that time. What would the experienced general do now?

(For those who don’t know, the “Black Hand” was a Serbian nationalist organization whose assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand started the First World War).

When King Qingxiang opened the gates to his capital, Bai Qi’s troops flooded into the city. The treasury was looted, and the ancestral tombs were desecrated. Many nobles were captured, and King Qingxiang himself fled eastward. His rump court set up a new capital at Chen (陈). Bai Qi’s advance ended at Ying, but by that point, all of Chu’s northwestern riches had already fallen under Qin rule.

This is now the state of affairs in China. Chu and Qi are severely weakened. Zhao is the only state that can threaten Qin’s dominance.

The Battle of Changping

In most cases, a single battle doesn’t deserve its own section. But the Battle of Changping (长平之战) is probably as influential for Chinese history as the Milvian Bridge was for the spread of Christianity in Europe. So let’s discuss it in depth.

Quick recap. When the vertical alliance system collapsed, every state turned on every other state, and it became a free-for-all. In this bloody melee, Qin became the most powerful, mostly due to Shang Yang’s centralizing reforms. The once-mighty states of Qi and Chu both experienced devastating setbacks that severely weakened their power. By 262 BC, only Zhao, under its ruler King Xiaocheng (赵孝成王), was capable of resisting Qin.

Zhao's power largely rested on two men. First was the old and highly experienced general, Lian Po (廉颇). The other was its prime minister, Lin Xiangru (蔺相如). If any general had the military genius of the Qin general Bai Qi, it was Lian Po. If anyone had the vocal dexterity of the late Zhang Yi, it was Lin Xiangru. As long as these two bastions lived, Qin’s dreams of unifying China would never come to fruition.

In 270 BC, an official who had fled from…Wei (how can one bureaucracy have such terrible retention rates?) arrived in the Qin capital, Xianyang. He received an audience with the king, and advised him to implement a policy called “Yuanjiao Jingong” (远交近攻), or allying with distant states and attacking nearby ones. Adopting this advice, during the 260s BC, Qin signed a peace treaty with Qi, and attacked Han and Wei repeatedly, forcing them to cede large amounts of territory.

In 262 BC, Qin attacked Han again, cutting off the seventeen cities of Shangdang Province (上党郡) from the rest of the kingdom. To reach a peace, the King of Han agreed to cede all seventeen cities to the Qin kingdom. The province’s governor, however, not wanting to submit to Qin, surrendered his territory to Zhao instead.

Qin was horrified. The Qin king sent Bai Qi and his massive army into Zhao to “convince” them to hand the province over. The Zhao king responded by sending a massive army under Lian Po to counter the threat. In total, a combined 1 million soldiers were stationed on both banks of the Dan River (丹水) by the time deployment was complete.

Over the next two years, the numerically inferior Zhao army held on, stubbornly refusing to launch any offensives despite repeated enemy provocations. However, as the war raged on, the King of Zhao began to grow uneasy about the duration of the conflict. So, in 260 BC, he replaced Lian Po with Zhao Kuo (赵括).

Zhao Kuo was the son of a great general, Zhao She (赵奢), and an avid peruser of military texts. However, he had no battlefield experience whatsoever. One night, the king invited Zhao to his palace to seek his opinion on the war, and was impressed by how effortlessly quotes from military handbooks (including, of course, Sun Tzu’s Art of War) slipped off his tongue. So, King Xiaocheng, against the advice of multiple advisors, and even Zhao Kuo’s own mother, appointed him supreme commander. This story would come to have its own idiom: 纸上谈兵, or being proficient with military strategy only on paper.

So now Zhao Kuo is in charge. Word of warning: the next part may inspire a lot of cringing and face-slapping.

The second Zhao Kuo took command, he launched a headlong assault at the enemy's left flank, which he thought was weak. That flank retreated, bolstering his confidence, and causing him to order the rest of the army to cross the river to exploit the weakness. When his advisors warned him of encirclement, he brought up the Art of War, arguing that according to Sun Tzu, the enemy would need at least ten times the number of troops he had to complete such an encirclement.

The day waned as the Qin forces led Zhao Kuo’s army into a valley. Suddenly, the Qin army stopped fleeing. From the high ground, they hunkered down into defensive positions. As Zhao was about to order an all-out assault to dislodge them, the sound of war drums erupted from the North and South. Before the Zhao army could even wheel around, Bai Qi’s forces blocked off the two remaining exits to the valley. Bai Qi’s triangular encirclement was complete.

Now, when I say a word like ‘valley,’ you may imagine lush green grass, vast fields, and a gently flowing creek. But Bai Qi had done his homework, and the valley he trapped his enemies in was narrow, desolate, and most importantly, cut off from water. Zhao Kuo, who had previously shunned his advisors’ advice not to be reckless, now begged those same advisors for a plan. None could come up with one. For many days, the Zhao army launched attacks in every direction, hoping to break out. But each time, the steepness of the cliffs and the exhaustion of the men forced them back. By some estimates, 250,000 Zhao soldiers and their commander were dead before the remaining remnants surrendered.

Did Bai Qi treat these captured soldiers well? Of course not!

In the most brutal massacre of the Warring States Period (and believe me, the competition for the top spot is fierce), Bai Qi ordered the 200,000 captured soldiers to be buried alive. When King Xiaocheng of Zhao heard about the devastating conclusion of the battle, he fainted on the spot. Bai Qi’s army then encircled the Zhao capital, Handan (邯郸). But in a rare show of unity among the eastern kingdoms, every single one sent troops to relieve the city, and Bai was repelled. But Zhao had lost all semblance of a great power.

Max Facts! The phrase 百足之虫,死而不僵 literally translates to “a bug with a hundred feet keeps on moving even when dead.” This disgusting yet commonly-used saying in the Chinese language is used to describe kingdoms or polities that were once powerful, but have now been shattered, and may still survive for some time, but are essentially on the path to collapse.

On another note, throughout the period following the Battle of Changping, it’s not like Qin was utterly undefeated. There was still some back and forth between Qin and the other six nations in the East. However, none could pose a real threat to Qin’s dominance, and over the next half-century, Qin would gradually expand at the expense of the other kingdoms.

The only state capable of resisting Qin was now essentially a dead centipede. Its legs still moved, but its heart had stopped pumping.

On a side note, from 256-255 BC, Qin conquered the remaining territories of Zhou (周), which had now split into East and West. You probably didn’t even remember that this whole period was technically still the Zhou Dynasty! Well, now it isn’t anymore!

The End of Disunity: The Rise of King Zheng of Qin

If you’ve been playing the “who will win this battle royale” game since the beginning of the fifth blog post, you’ll be happy to know that the game ends here. As the caption likely revealed, Qin (秦) is the ultimate victor. Through a series of legalist reforms that centralized the state and disciplined its people through lavish rewards and harsh punishments, Qin became indomitable. Secluded behind the Hangu Pass, Qin could not be easily invaded, and indeed rarely suffered devastating territorial losses like the other powers did. The Battle of Changping (长平之战) sealed the deal, eliminating the only viable rival left.

However, for Qin to unify all of China, an ambitious leader was required. That leader would come in the form of King Zheng of Qin.

Ying Zheng (嬴政) was born in the kingdom of Zhao. He was the son of King Zhuangxiang of Qin, but was living in Handan as a hostage. In 247 BC, when the king passed away, Ying Zheng, with the help of an advisor, Lu Buwei (吕不韦), returned home and ascended to the throne.

You’re probably wondering right now: how could a future king be a hostage in a foreign kingdom? Back in ancient China, it was quite customary to send members of the royal family to foreign kingdoms as hostages. Of course, how well your hostages were treated depended heavily on the strength of your kingdom, but it was not uncommon to have even crown princes be sent off as hostages. Royal families were not very familiar with the concept of familial love

King Zheng of Qin would become the most famous ruler in Chinese history. “But wait! I’ve never heard of King Zheng!” you’re probably thinking. That’s because Ying Zheng did not want to be remembered by that name. He wanted to die as something greater.

Conquest of Han

In 230 BC, King Zheng sent out an army of 100,000 elite troops to conquer Han (韩), the smallest of the kingdoms. Over the years, it had repeatedly ceded land to various kingdoms around it to keep from being invaded, moves which gradually weakened the already feeble state. 100,000 was only a fraction of Qin’s total manpower, yet even so, King An of Han (韩王安) couldn’t muster more than a mere 80,000 under-equipped troops, few of which were in their prime, to counter the threat. Han was easily defeated, and its territory was incorporated as a province in the Qin Empire.

Conquest of Zhao

Qin next turned its gaze to Zhao (赵), which was not totally defenseless despite losing a massive army at Changping. For some reason, rather than keeping its remaining forces at home, it was still busy invading its weaker neighbors in hopes of restoring its former glory. In 236 BC, Zhao launched a massive invasion of Yan to its East. In doing so, it left its western border virtually undefended. Qin seized the opportunity, and captured multiple border towns, sending the Zhao court into a frenzy. But when Qin tried to move further, Zhao general Li Mu (李牧) shocked his opponents by actually defeating them. Between 230 BC and 229 BC, Li Mu fought the bulk of the Qin army to a standstill, and although a second Qin army had taken a different route to reach and besiege the Zhao capital Handan (邯郸), the situation was far from hopeless.

But then, an old habit of Zhao rulers kicked in.

Through some delicate negotiations (a.k.a bribery), the Qin managed to get the Zhao government (namely, the king’s mom) to replace Li Mu with a more aggressive general.

Can you imagine how powerful Zhao could have been without these ill-advised replacements? At Changping, the Zhao army was doing great until the king replaced the reserved Lian Po with the aggressive Zhao Kuo. Will the replacement of Li Mu have the same repercussions?

Spoiler: Yes. Another whole Zhao army was annihilated. And this time, King Zheng was out for the kill. That same year, Handan fell, and Zhao was officially annexed into Qin. Though a member of the royal family, Prince Jia, would declare himself the King of Dai (代王) in what remained of the kingdom’s northeastern holdings, that stub of a state would be conquered in 222 BC. The once-great powerhouse of the North was no more.

The Conquest of Wei

Following the conquests of Zhao and Han, Qin moved on the kingdom between them: Wei (魏). Wei was far from the kingdom it was during its glory days under Pang Juan. It could only muster 100,000 soldiers to defend its territory, and even then, these troops could only hide behind its capital, Daliang’s (大梁) walls. Qin sent 100,000 elite soldiers under General Wang Ben (王贲) to encircle that city.

But Daliang was a tough nut to crack. Its walls were not only thick from decades of reinforcement, but also strategically located. Built at the intersection of three rivers, the city essentially had a natural, near-impassable moat. Wang Ben found himself attempting to beat these immense odds for many months, to no avail.

So as many people do when they get stuck, Wang Ben turned to history as a guide:

Flooding! Wang Ben’s aha moment came at the detriment of the city’s residents. Through some careful planning, Wang Ben’s engineers guided the rivers’ waters to flood through the city gates, causing hundreds of thousands of civilians to drown. The survivors fled to the royal palace, which was on higher ground. As the days passed, even this final fortress was losing its fight to the rising tide. King Jia of Wei (魏王假), seeing that the situation was hopeless, and wanting to end the suffering, soon surrendered.

Meanwhile…

Conquest of Chu

The invasion of Wei provided coverage on the flanks for the main objective of Qin’s eastward expansion in 225 BC: conquering Chu (楚). However, the bastion of King Zhuang would be harder to vanquish than even the three Jins combined. What would Qin do?

Li Xin (李信) and Meng Tian (蒙恬) had an idea. “We can conquer Chu with a force of just 200,000!” they claimed. “Just?” You may be asking. Yes. Because an older general by the name of Wang Jian (王翦) had proposed raising a force of 600,000 to achieve this objective.

King Zheng was delighted by Li and Meng’s proposal, and immediately approved their invasion. There’s no way that their proposal would prove overconfident and overaggressive, right?

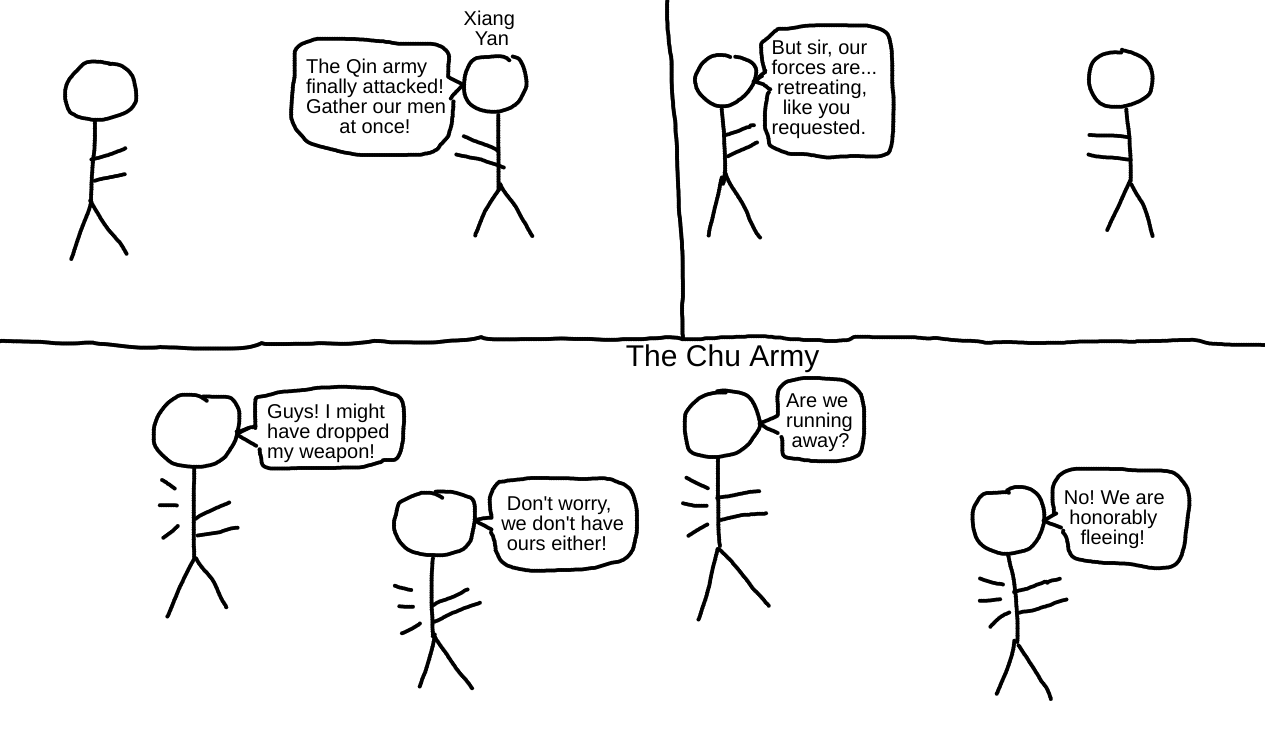

Chu used the oldest trick in the book to trounce their enemy. After a few early victories, Li and Meng expanded with pride. Little did they know that a general Xiang Yan (项燕) was following them throughout the campaign. When the two Qin generals merged their forces, and encamped for the night, Xiang Yan struck, annihilating the force. Li Xin and Meng Tian barely made it out alive.

The next year, King Zheng, never one to give up, gave Wang Jian what he wanted: 600,000 troops to conquer Chu.

Now, if you know the first thing about ancient politics, you’d know that the man (or occasionally, woman) who controlled the military also held significant sway in politics. With his entire army now in the hands of a single general, King Zheng was extremely fearful of a military coup.

How would Wang respond to these concerns? Well, every few days while he was off campaigning, he’d write back to King Zheng asking for some lavish gift. “I’d like a new mansion for my son! A nice garden with a waterfall for my daughter! The newest model of wagon for my wife!” Each time, King Zheng approved them willingly. Wang’s requests showed that he did not seek political power, just a luxurious retirement after the war was done. After a few months of this, King Zheng was satisfied with Wang Jian’s loyalty, and stopped meddling in the campaign.

Xiang Yan was once again sent out to counter Qin’s forces, this time with the remaining forces Chu could call upon: 400,000 elite and reserve troops. But Xiang Yan was no Lian Po. Despite his army’s numerical inferiority, he kept trying to lure his opponents out into open battle. When his repeated overtures failed, he ordered a retreat. And that was when Wang struck.

Max Facts! While earlier, I wrote that Yue (越) was annexed into Chu, that is not fully true. After destroying Yue’s forces, Chu had turned it into a client state beholden to its conqueror. After Chu fell, Qin steamrolled the Yue army the next year, conquering the entire South.

The surprise attack caught the Chu army off guard, forcing them to flee. Xiang Yan retreated with his men, and died under the sword of a pursuing infantryman. His army was annihilated, and with it, the final spark of hope for the ailing kingdom. In 223 BC, Chu was annexed into Qin.

The Conquest of Yan

The kingdom of Yan (燕) was Qin’s next target. But before Qin made any moves, Yan panicked first. Namely, its crown prince, Dan (太子丹), panicked. In 227 BC, he hired an assassin named Jing Ke (荆轲) to do the impossible: assassinate King Zheng.

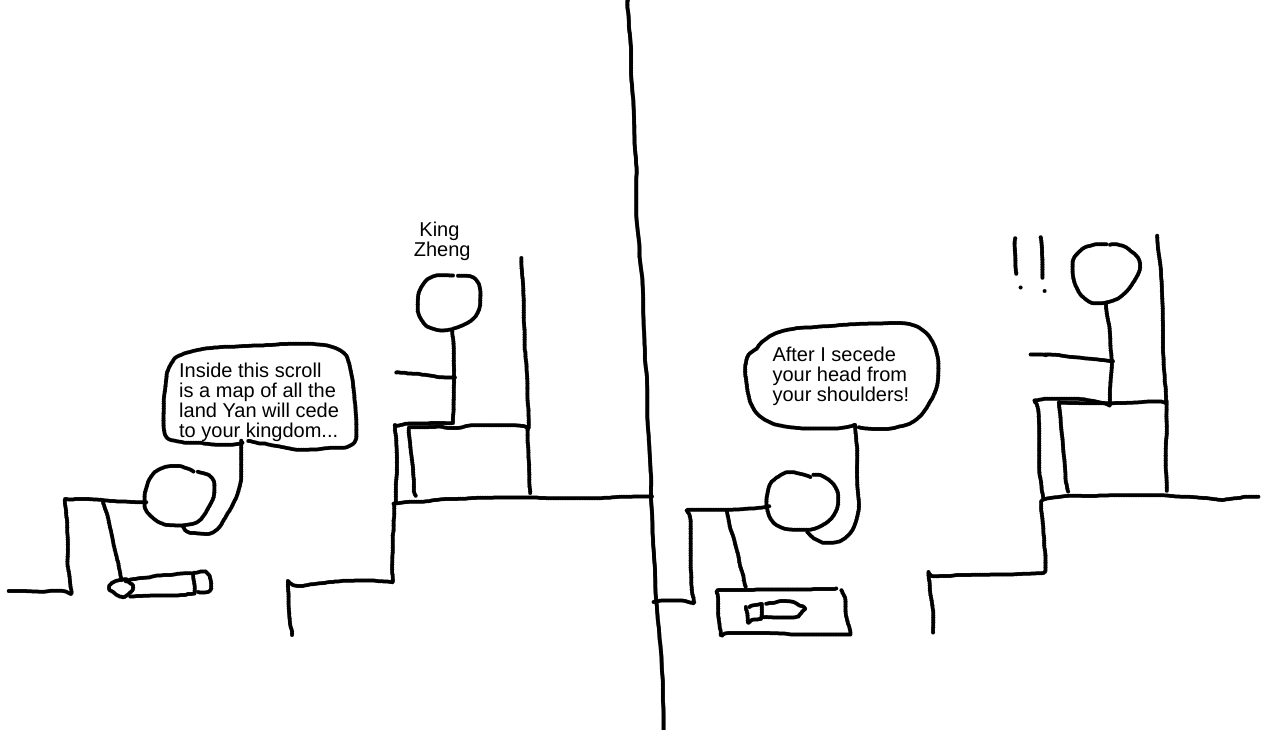

How would Jing do it? It all centers around a map—a map of all the cities that Yan was prepared to “cede” to Qin in exchange for peace.

The story goes that after Jing Ke unfurled his map before the entire court, a dagger laced with deadly poison was revealed. Jing seized his dagger and lunged at the king. King Zheng turned and fled, and soon, the two were having a merry chase around a massive pole. Hundreds of armed guards stood right outside the palace gates, but by law, they were not allowed to enter unless summoned by the king. And in his panic, the king failed to summon them.

Jing Ke slashed repeatedly at King Zheng, falling just a little short each time. Each courtier and bureaucrat looked on in shock, but none rushed to their monarch’s aid. But a brave doctor who was standing nearby, witnessing the situation, took a medicine pack that was on him and hurled it at the assailant. Jing raised his hand to block the attack, giving King Zheng a split second to maneuver. Rearing his head a little, King Zheng tore his imperial longsword from its sheath and slashed off one arm and one leg from his pursuer. The useless guards were finally summoned, and they hacked Jing to pieces.

In 222 BC, a 200,000-strong Qin army under Wang Ben (王贲) brutally massacred the Yan forces, and conquered that kingdom.

Conquest of Qi

Qi (齐) remains. As its neighbors fell, the King of Qi did nothing to assist them. “So what if they fall,” he thought. “We are the land of Jiang Ziya! We have hundreds of thousands of soldiers at our disposal! Qin can never take us down!”

The problem was that Qi’s massive army was underequipped, unprofessional, and thus not ready for war. After all, due to their monarch’s “masterful inaction,” they were given no opportunities to gain battlefield experience. But hey, there’s a first time for everything, right?

In 221 BC, King Jian of Qi (齐王健), seeing that all the other kingdoms were now gone, finally recognized the gravity of the situation. He ordered the entire kingdom’s forces to form two lines of defense facing the west, to counter what he believed would be the main thrust of Qin’s offensive.

What he failed to realize was that Wang Ben’s (王贲) army, which had just finished conquering Yan, was now positioned directly North of his capital, Linzi (临淄). So Wang simply turned his army south, and arrived virtually unopposed before Linzi’s gates.

Linzi’s defenders were outnumbered 40-1. King Jian of Qi had no choice but to surrender.

Non-Qin Kingdoms’ Status: Eliminated!

After 500 years of division, the surrender of Qi in 221 BC marked the ultimate denouement of the Warring States Period.

That same year, King Zheng declared himself Qin Shihuangdi (秦始皇帝), or “first emperor of Qin.” From the ashes of the Zhou Dynasty, the Qin Dynasty was born.

TO BE CONTINUED...

Bonus: Three years after the ascension of Ying Zheng as emperor...

218 BC

Leave a Comment

Comments